Ventura County sells itself as polished, safe, and righteous. Good schools, “family values,” and public institutions that supposedly function with professionalism and integrity. But beneath that carefully managed image is a darker reality, an insulated political ecosystem where government agencies protect each other first, and the truth comes last.

That is what Greg Dettorre says happened to him. A teacher. A father. A man who insists he never laid a hand on his children, never committed a crime, and was never charged or arrested for abuse, yet still became the target of what he describes as a coordinated, premeditated campaign involving the Sheriff’s Office, CPS, and the District Attorney’s Office.

Dettorre’s story isn’t just about a custody dispute or a contentious divorce. It’s about power. It’s about law enforcement being weaponized. It’s about bureaucratic institutions acting like a cartel, closing ranks to bury misconduct, destroy reputations, and silence anyone who refuses to play along.

The moment he says he knew his life was about to be dismantled came on Friday, January 24, 2020. Dettorre received a phone call from Ventura County CPS whistleblower Charity Cox, who had been placed in charge of abuse allegations tied to Dettorre’s ex-wife.

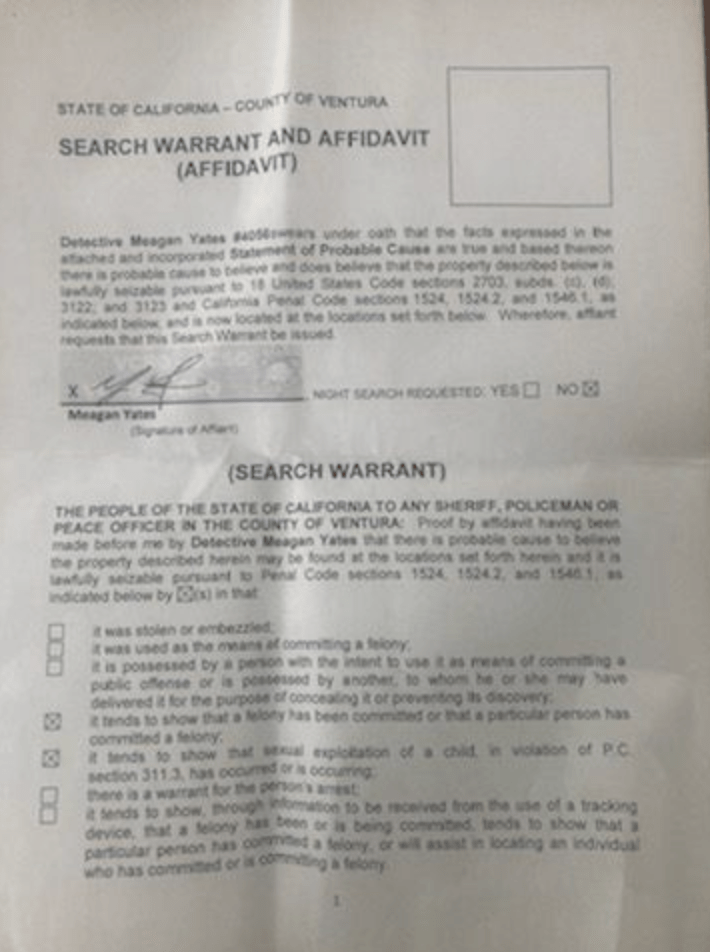

According to Dettorre, the call was brief but chilling. Cox allegedly told him Detective Meagan Yates pressured her to alter the results of her report. Four days later, Dettorre says the Ventura County Major Crimes Unit executed a warrant on his parents’ home, where he was living after the divorce. From that point forward, he believed the system had made its decision.

Dettorre maintains he has never been charged with or arrested for any crime related to his daughters, or any other child. Not once. Yet he alleges the Ventura County Superior Court and its allies inside the Sheriff’s Office and District Attorney’s Office suppressed and/or destroyed evidence to ensure the truth never surfaced. Not because the evidence supported guilt, but because the machinery depends on narrative, not justice.

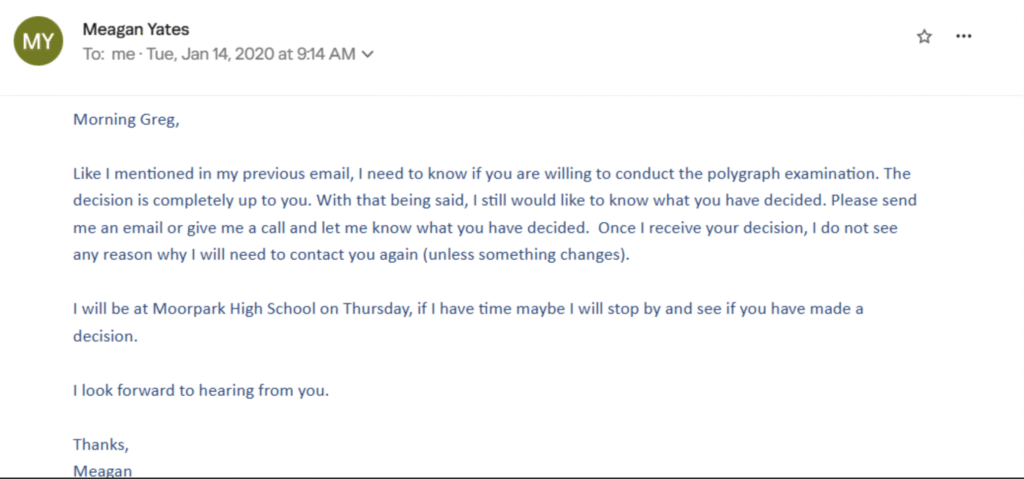

At the center of Dettorre’s allegations is Detective Meagan Yates, a name he says represents everything rotten about the “Ventura County Corruption Machine.” He claims Yates pursued him with a fixation that was not rooted in evidence, but in agenda, an agenda he believes was aligned with his ex-wife from the start.

Dettorre alleges Yates and his ex-wife had improper contact for years before and after the investigation. He describes it as an “open secret” that even third parties knew about, including the children’s therapist, Nancy Lopez, who allegedly contacted him to say Yates remained involved. If true, this isn’t a harmless ethical lapse. This is case contamination. It is the kind of relationship that makes every decision suspect and every action look premeditated.

This wasn’t even the beginning of Yates’ involvement in Dettore’s life. Years before the alleged abuse investigation, Yates responded to a 911 self-harm call Dettorre made in October 2017, at his home in Moorpark, during what he describes as an unbearable collapse; bankruptcy, loss of his home, and his ex-wife fleeing with their twin daughters.

He expected medical assistance. Instead, he says he was met by then-Deputy Meagan Yates pointing her service weapon at his face. Dettorre describes the moment as both humiliating and defining, because it established a personal, adversarial connection between him and the very person who would later investigate him.

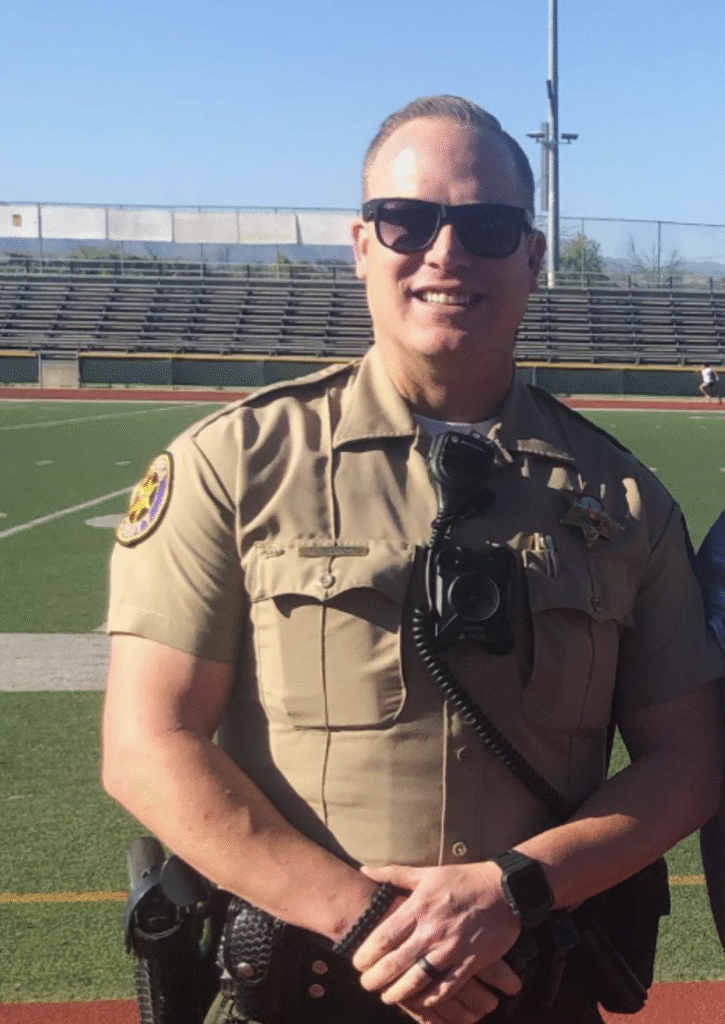

Then comes the conflict of interest that Ventura County allegedly ignored entirely. Yates wasn’t just a detective assigned to a case. She was also the Campus Resource Officer for the Moorpark Unified School District, the same district that hired Dettorre as an engineering teacher in December 2018.

That means the investigator and the target existed in the same school district ecosystem at the same time. A man’s future, his employment, his reputation, and his children’s lives were put in the hands of someone who had already confronted him during a mental health crisis, and who was professionally linked to the same institution employing him.

Any credible system would have recognized what this was and removed her immediately. Not because of politics. Not because of public pressure. Because ethics and due process demand it. But Dettorre alleges Ventura County isn’t built for fairness. It’s built for control.

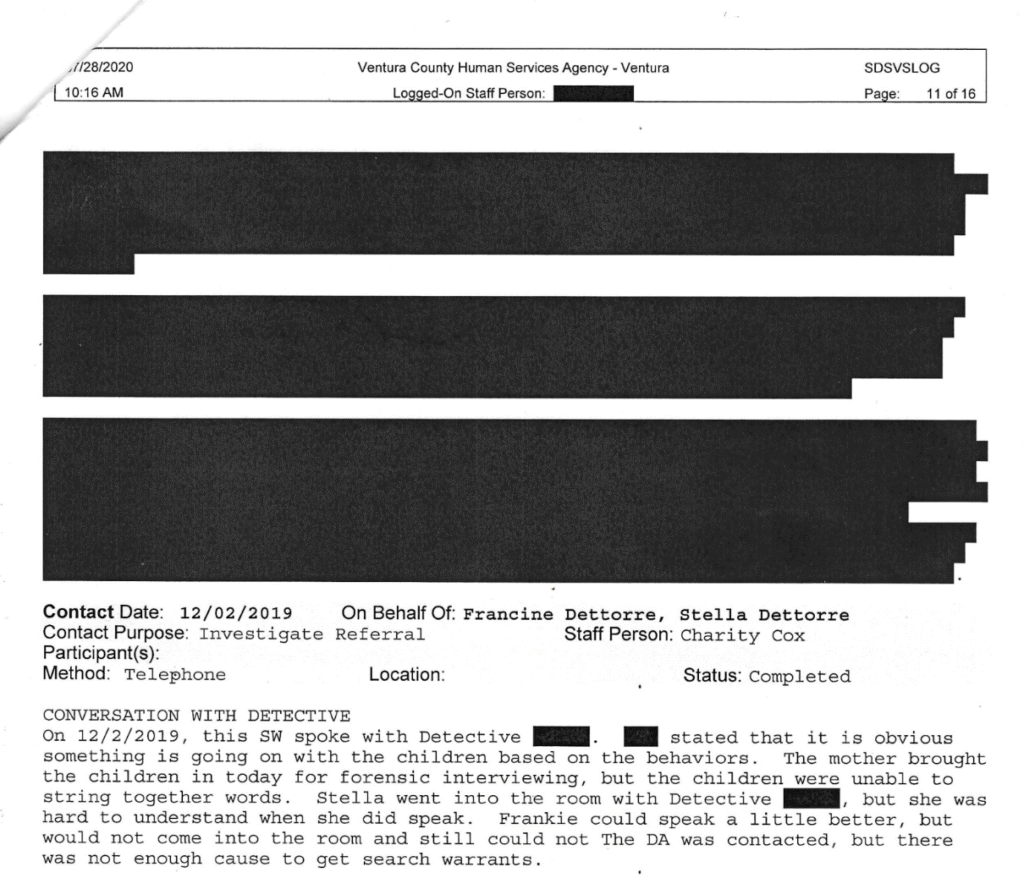

Dettorre claims Yates began attempting to build a case against him months before the warrant was executed. He says she initiated the effort in September 2019 and was eventually told in December of 2019 by the District Attorney’s Office, then under Greg Totten, that Yates lacked cause for a search warrant. Despite the accuser alleging the children were making sentence long statements against their father, the children, who had just turned 2 years old, were documented to have little to no discernable speech in the forensic examination.

If that is true, it should have ended there. It should have died quietly like countless other weak allegations that fail under scrutiny. But Dettorre says Yates simply found another route, using CPS as a workaround to restart efforts to secure a search warrant that the DA’s office allegedly denied her.

Days after being denied the search warrant, Dettorre alleges Yates encouraged his ex-wife to re-ignite the allegations through CPS. The CPS complaint again alleges that the children were describing abuse in sentence-long detail, contradictory to the fact that the children were documented 2 weeks prior in a forensic examination, with Yates present, to have little to no speech ability.

Despite the fact that this allegation conflicted with reality, Yates used it to keep the investigation open. In other words, the same person who couldn’t get traction through normal investigative channels allegedly leveraged provably false statements through a different agency to get the outcome she wanted.

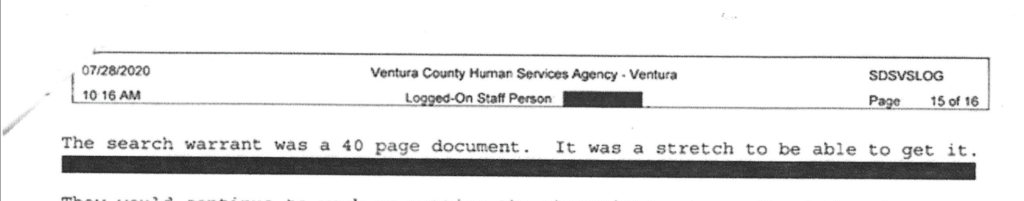

Dettorre believes this was not sloppy procedure. He claims it was premeditated misconduct, a deliberate act intended to manipulate the system into granting an emergency warrant. He alleges the CPS report was altered to support the appearance of urgency, not because there was genuine danger, but because urgency is the easiest way to short-circuit accountability.

And even with that, Dettorre says Yates needed more. She needed law enforcement testimony to help secure the warrant affidavit. She needed other uniforms to validate the story. She needed the system to echo itself, so the paperwork looked legitimate.

Dettorre alleges Yates harassed him relentlessly, including sending Dettorre an email threatening to appear at the Moorpark campus while he was teaching and interrogate him in front of students about abuse allegations. That isn’t policing. That is intimidation. That is public humiliation as strategy. Dettorre says he was forced to retain a criminal defense attorney simply to protect himself from the Sheriff’s Office, and to keep Yates from harassing him in front of his students on the Moorpark Campus.

Then something happened that Dettorre says confirms the operation was already in motion. At the exact time and date Yates allegedly threatened to show up at the school on January 16, 2020, a Moorpark campus deputy, Marc Riggs, entered Dettorre’s classroom, escorted by Assistant Principal Tara Thomas.

Dettorre describes Riggs as armed, uniformed, and lingering in the classroom for two hours while asking vague questions about Dettorre’s family and even questioning students about whether Dettorre was a “good guy.” Riggs allegedly wandered in circles, repeatedly talking about how much he wanted to volunteer in the class but couldn’t. Dettorre says the entire encounter felt staged, unnatural, and designed to provoke fear while collecting “character” information that could be later used to justify action.

Dettorre believes Riggs’ involvement extended beyond the classroom, possibly into sworn testimony supporting the search warrant affidavit. He cannot confirm it, he says, because the Sheriff’s Office refuses to turn over the case file—despite Dettorre never being charged or arrested.

Dettorre believes Cox, despite being strong-armed by Yates to alter her results, was still trying to do the right thing by tipping-off Dettorre about the altered CPS documents. Cox, within the CPS report, described the warrant as follows:

“It was a 40 page document. It was a stretch to get it”.

Dettorre alleges that “stretch” was Yates changing the results of a CPS investigation to secure the warrant.

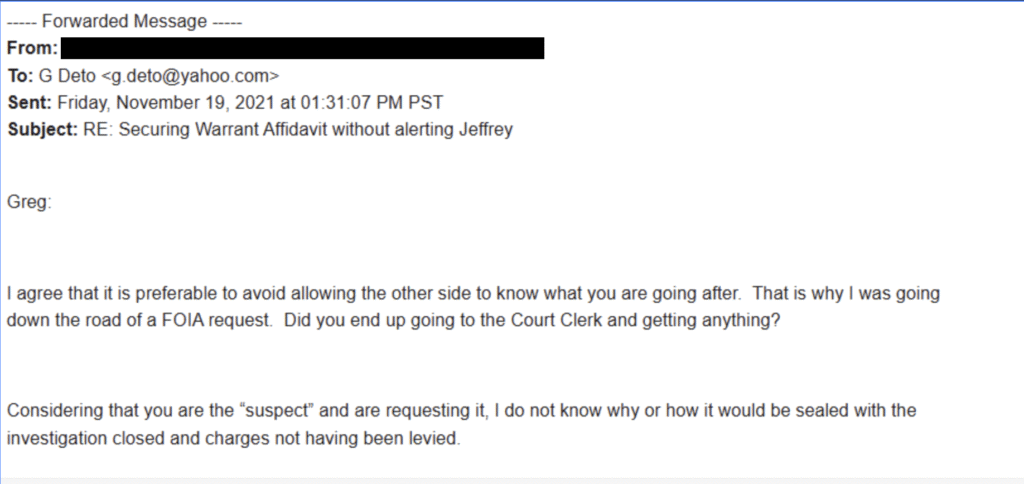

When Mr. Dettorre’s lawyer at the time attempted to retrieve the case file in 2021, the S.O.’s justification for withholding it was that the case file was sealed, despite the fact that there were no charges levied.

That refusal, Dettorre argues, is the loudest confession Ventura County could make. The Sheriff’s Office Clerk’s in-person response to Dettorre, moths prior to his lawyer’s email communication with the S.O., claimed that it was a CPS investigation, not a Sheriff’s investigation, therefore the records are not theirs to provide.

But reality makes that excuse laughable. It wasn’t CPS who raided a home with armored personnel. It wasn’t CPS who executed a warrant. It wasn’t CPS who brought force and intimidation to Dettorre’s doorstep.

That was the Ventura County Sheriff’s Department. And they know it.

The deeper link between the Sheriff’s Office and Moorpark Unified School District makes the story even more disturbing. When the warrant was executed, Dettorre was living in his parents’ home. His father, Scott Dettorre, was listed as a suspect too.

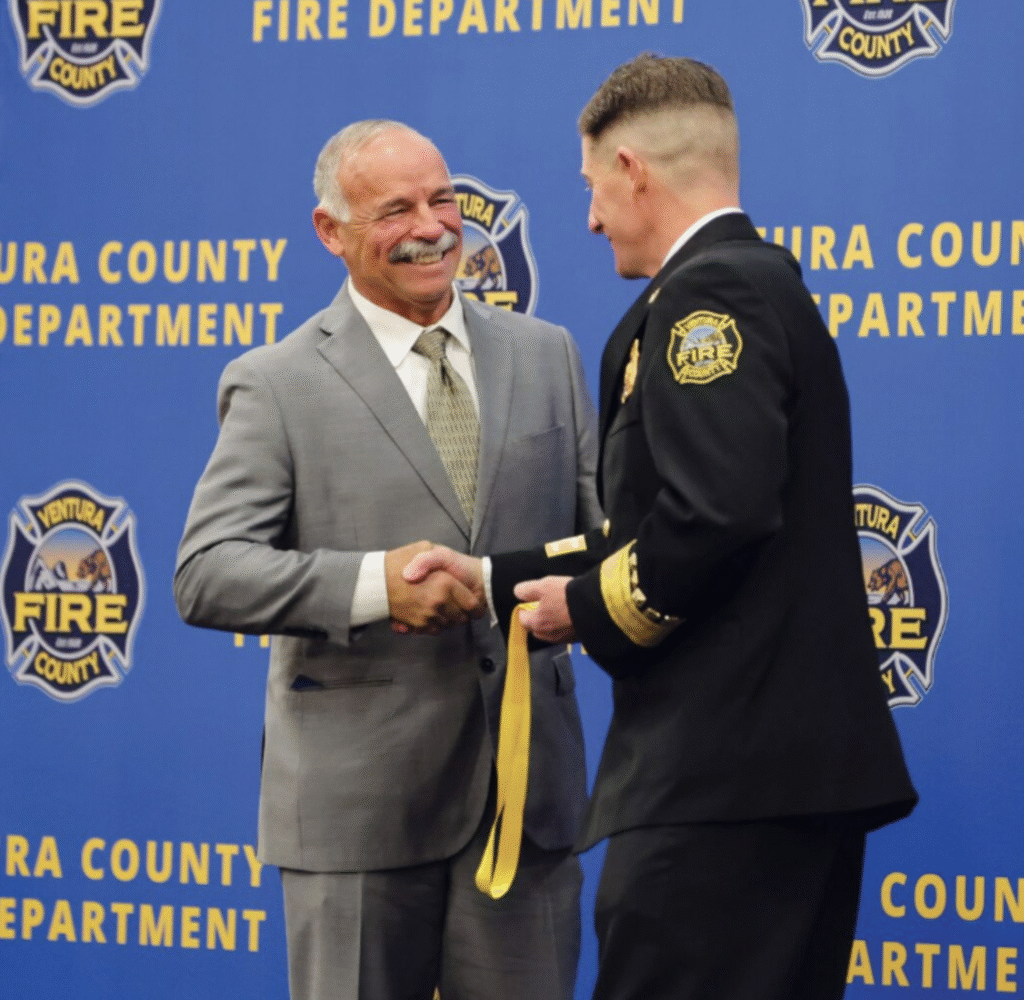

Scott Dettorre, a respected, decorated, and recently retired Fire Captain of the Ventura County Fire Department who spent 30 years with the organization, was the Moorpark Unified School District Board President at the time.

According to the warrant receipt and email communication documented in the CPS report, Yates believed beyond any shadow of a doubt that the children were being abused.

Through documented communication within the CPS report, Cox wrote the “Detective stated that it’s obvious something is going on with their (children’s) behaviors.”

The list of justification for arresting a suspect on-site when executing the warrant is lengthy. This even includes an “unnatural interest in children’s activities.” According to Dettorre, Yates recovered over a decade’s worth of internet-connected devices, including phones, tablets, computers, and hard drives.

If there was one instance of wrongdoing by Dettorre, even logging into a chat room where minors convene, he would have been arrested on the spot. In the end, Yates had absolutely nothing and was now forced to close the investigation four months later, on May 19, 2020.

Ironically, the Dettorre family approached the S.O. immediately following Yates’ closure of the case and begged them to keep the investigation open to find the children’s true abuser.

The Dettorre family agreed that the children were showing signs of exploitation, and wanted the abuser brought to justice.

Under the failed leadership of then-Sheriff Bill Ayub, the department refused to investigate the case further. If Yates swore on a warrant affidavit that the children were being exploited and abused, why was she, or her superiors within the department, not interested in finding the perpetrator?

Why was there no investigation into the accuser after Dettorre was cleared?

Because it didn’t fit the narrative. For Yates, if she was unable to arrest Dettorre, then there was no other abuser.

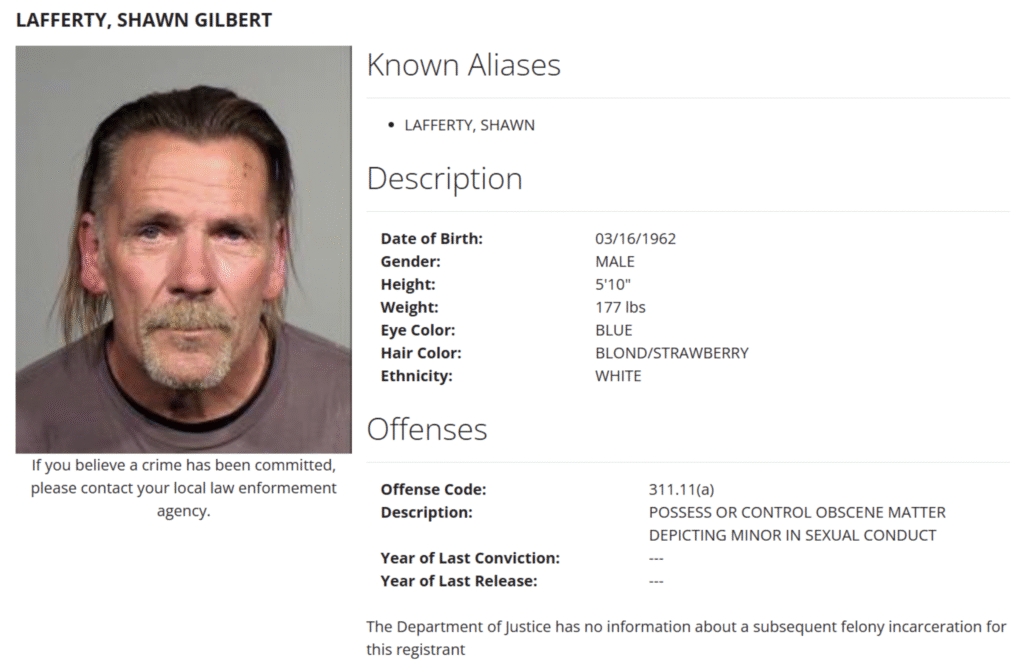

The next part will churn any parent’s stomach: The accuser’s maternal uncle, a twice arrested registered sex offender who visited the children regularly, was not considered a suspect by Yates.

The accuser’s allegations started at nearly the same time that her uncle, Shawn Lafferty, who lived less than two miles from the accuser’s home, was arrested for a second time in a D.A. sweep of registered offenders for possession of child pornography.

Somehow, even after his second arrest for possession of child pornography, Yates did not consider him a suspect, and Lafferty still remains free to roam the county, living on a boat in Channel Islands Harbor.

Tragically, Dettorre is unsurprised by the continued failure of the Ventura County D.A.’s office to protect children, citing Erik Nasarenko’s refusal to charge Ventura City Attorney Andrew Heglund for allegedly exposing himself to children inside a Chik-Fil-A.

Dettorre asserts that if the investigation had been continued by an ethical detective, it could have led to Lafferty, but this was a politically unacceptable outcome for both the D.A.’s office as well as the S.O.

If a twice-arrested sex offender was arrested for crimes against Dettorre’s daughters, it would have started an avalanche of both legal and political liability for both law enforcement agencies.

A case involving a detective tied to the Moorpark School District, a teacher employed by the district, a campus deputy appearing inside the classroom, and then a warrant executed at the home of the sitting school board president is not “random.” It is not “routine.” It is not coincidence.

It looks like institutional muscle being flexed against a target who refused to submit, and against a family the system decided to punish.

Dettorre says the end result is exactly what Ventura County’s machine was designed to produce: no accountability for government actors, no transparency for the public, and maximum devastation for the individual standing in the way.

He lost his career. He lost his life as he knew it. And most painfully, he lost his daughters, not because he was convicted, not because he was charged, but because once the corruption machine starts moving, it doesn’t need proof. It only needs compliance.

And in Ventura County, compliance is the currency.

Follow Us