For the second time in as many months, John Ackerman, the appointed General Manager of Los Angeles World Airports, has advanced a proposal that would significantly expand his personal authority while narrowing the role of the LAWA Board of Airport Commissioners. The item, scheduled for consideration at the Board’s February 19, 2026 meeting, is framed as a technical delegation of authority. In substance, it represents a fundamental shift in governance that concentrates decision-making power inside the executive office of LAWA and diminishes the independent oversight role the City Charter assigns to the Board.

Ackerman does not hold elected office. He does not answer directly to voters. Yet the resolution before the Board would authorize him to make and enforce rules governing airport security, property use, and facilities across the LAWA system with minimal contemporaneous oversight. The Board would receive reports only after the fact, twice a year, while actions taken under that authority would become final pursuant to Charter Section 245. The practical effect is not efficiency but insulation, a governance structure in which decisions are implemented first and scrutinized later, if at all.

The City Charter is explicit about how authority is allocated and how it may be altered. Structural changes to governance do not occur through internal resolutions or administrative delegation. They require approval by the people of Los Angeles through a ballot initiative or an ordinance placed on the ballot after a petition process. What is being proposed here follows neither route. Instead, it relies on selective readings of delegation provisions to achieve what amounts to a charter-level power transfer without voter consent.

The urgency of this debate cannot be separated from Ackerman’s record since taking the helm at LAWA. His tenure has been marked by sustained conflict with city labor unions, not only over policy direction but over compliance with labor law itself. Several disputes have escalated into formal Unfair Employee Relations Practice complaints filed with the city’s Employee Relations Board, alleging violations of collective bargaining obligations and statutory protections. These are not abstract disagreements. They are legal challenges rooted in contested decisions affecting wages, working conditions, and job security.

Ackerman has consistently described labor protections and oversight requirements as impediments to progress, invoking the language of “red tape” to justify sweeping managerial discretion. That framing is central to understanding why unions view the proposed delegation as a threat. Once authority is centralized in the CEO’s office, decisions that reshape the workforce can be made unilaterally, shielded from meaningful Board debate, and presented to the public only after they are effectively irreversible.

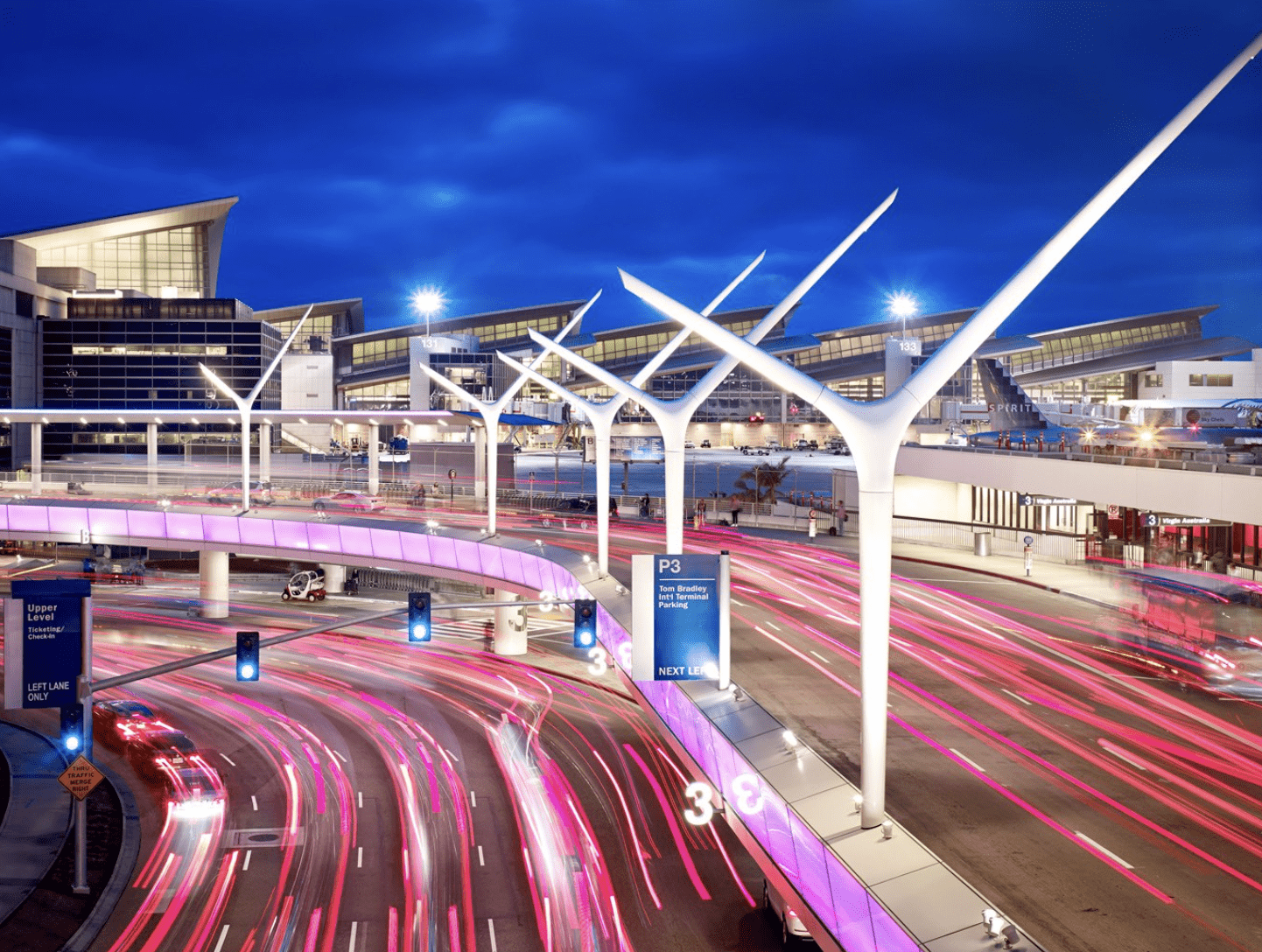

This consolidation of power is unfolding at a moment when LAWA’s operational and financial performance is already under strain. According to the Los Angeles Business Journal’s No Fly Zone report, passenger traffic across Southern California airports declined in 2025 compared with 2024, marking the first year-over-year drop since the pandemic. LAX itself experienced a notable decrease, contributing to a broader regional downturn that left Los Angeles-area airports lagging behind national recovery trends. The decline has been significant enough that LAX has fallen out of the top ten busiest airports in the world, a symbolic and substantive blow to its long-standing status as a global aviation hub.

The timing is especially consequential because LAWA is in the midst of one of the most expensive public infrastructure efforts in the country. Its modernization program, once projected at roughly fifteen billion dollars, has grown to more than thirty billion dollars, with major projects running behind schedule and well over budget. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Automated People Mover, the project long touted as the connective spine of the LAX modernization effort.

Originally budgeted at approximately $4.9 billion, the People Mover has faced repeated delays and escalating costs, with some estimates placing the overruns near nine hundred million dollars. The project is being delivered by LAX Integrated Express Solutions, a joint venture composed of some of the largest infrastructure firms in the world, including ACS, Alstom, Balfour Beatty, Fluor, and Hochtief. Despite the scale and sophistication of that consortium, the project has struggled to meet timelines and cost projections.

Legal and contractual disputes have played a significant role in those delays. Although LAWA and the consortium reached a settlement in early 2024 intended to resolve earlier claims, conflicts over maintenance responsibilities, compensation, and revised schedules have continued to surface. Each dispute has added friction to a project already under intense public scrutiny. Each delay has compounded costs. Each renegotiation has raised new questions about accountability and oversight.

This context matters because it exposes the contradiction at the heart of Ackerman’s push for expanded authority. The argument for centralization rests on the claim that oversight slows progress and inflates costs. Yet the most expensive and visible failures of the modernization effort have occurred under an already centralized project delivery structure, one that has required repeated legal intervention and renegotiation. Rather than demonstrating the virtues of unchecked executive control, the People Mover has become an example of what happens when complexity outpaces accountability.

At a time when passenger volumes are declining, costs are escalating, and flagship projects remain unfinished, the appropriate response would be heightened scrutiny and stronger governance. Instead, the proposal before the Board moves in the opposite direction, weakening the very mechanisms designed to interrogate assumptions, challenge timelines, and protect the public interest.

The promise of semiannual reporting does not substitute for real oversight. Reporting after decisions are made does not prevent miscalculations or mitigate labor conflict. It simply records outcomes once damage has already been done. Oversight that arrives too late is not oversight at all.

What is at stake in Thursday’s meeting is not a matter of administrative convenience. It is whether one of the most powerful public agencies in Los Angeles will continue to operate under a system of shared governance or drift toward executive rule by delegation. The City Charter was written to prevent that drift, recognizing that public institutions function best when authority is distributed, debated, and constrained.

Joe Martinez, a LAWA Construction Equipment Service Mechanic, warned that the resolution threatens far more than internal governance. Speaking ahead of Thursday’s vote, he said, “We oppose this resolution because it could threaten the vital services essential LAWA workers provide. With the World Cup and Olympics drawing in millions of people from across the world, we must ensure that all vital services are firing at all cylinders. Los Angeles is a world class city, our airport is a world class airport, and a world class airport deserves world class service.”

Los Angeles did not vote to place sweeping control of its airports in the hands of a single appointed manager. It voted for a structure that balances executive management with independent oversight and public accountability. Allowing that balance to be quietly dismantled, particularly at a moment of declining performance and mounting legal and labor disputes, sets a precedent that will extend far beyond LAX.

Once power is centralized, it rarely returns willingly to the bodies designed to check it. The warning signs are already present in labor unrest, legal challenges, ballooning project costs, and slipping global standing. The question now facing the Board of Airport Commissioners is whether it will affirm its role as a governing authority or voluntarily reduce itself to a body that merely receives reports.

Public agencies do not serve the public well when one office operates without meaningful restraint. The City Charter does not allow for kings. It was written to ensure there would be none.

Follow Us