From the moment Los Angeles County prosecutors arrived at the intersection of Triunfo Canyon and Saddle Mountain, the outcome was already decided. Rebecca Grossman was to be the villain, the symbol, the scapegoat.

The facts – messy, contradictory, inconvenient – were optional.

For more than four years, the District Attorney’s Office, led by George Gascón and fronted in court by Deputy DA Jamie Castro and Ryan Gould, constructed a narrative so airtight it couldn’t withstand oxygen. They needed malice to elevate a tragedy into a second-degree “Watson” murder, and they needed a villain to match their political ambitions. They got both by burying a man who could have upended it all.

Former professional baseball player Scott Erickson, a companion of Grossman’s, was not a peripheral figure in this story. He was the missing variable, the second car on surveillance video, the one that sped into the crosswalk seconds before Grossman’s SUV came into frame.

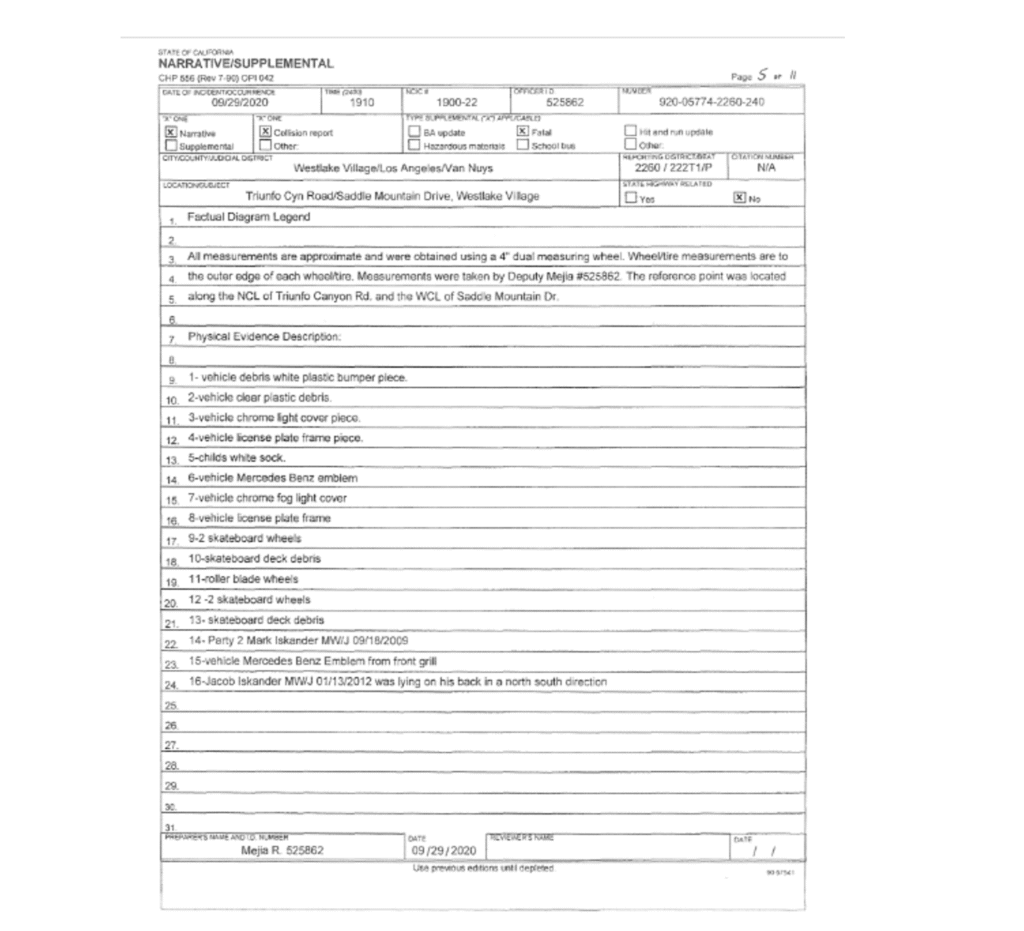

Vehicle fragments recovered from the scene, pieces consistent with the make and model of Erickson’s black Mercedes, were logged into evidence early in the investigation and later suspiciously went missing. The disappearance of those parts erased a direct forensic link that could have validated witness accounts of a second car. Compounding the issue, Erickson had been drinking earlier in the afternoon with former MLB player Royce Clayton, who later revealed that Erickson made incriminating statements about the crash that effectively ended their friendship. Clayton’s account on the witness stand during the criminal trial , along with the missing vehicle evidence, paints a deeply troubling picture of what investigators chose to ignore, and why.

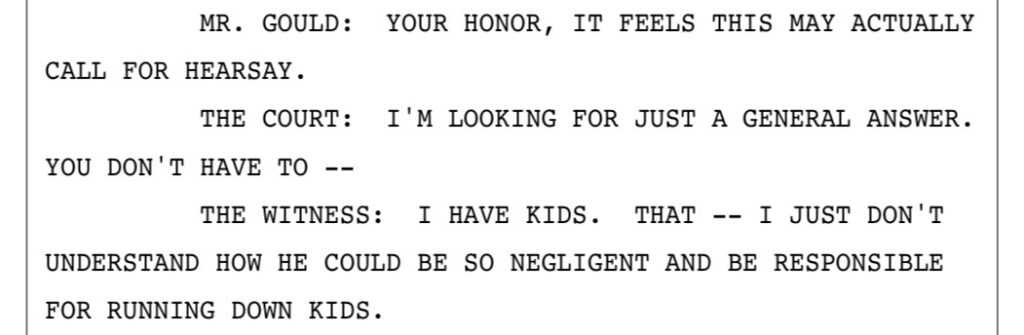

At trial, Castro mocked the idea that Erickson was anywhere near the scene, ridiculing Grossman’s daughter, Alexis, for testifying she saw him there. “A six-foot-four, 250-pound man hiding behind bushes?”

Castro sneered at the very suggestion, twisting it into a weapon. The insinuation was calculated and cruel, that Grossman had manipulated her own daughter into fabricating a phantom driver to shield herself from blame.

That attack resonated. It was repeated by self-styled “activist” Julie Denny Cohen who positioned herself early on as a spokesperson for the Iskander family, vilifying Grossman, her family members, and anyone who dared to challenge the prosecution’s narrative. She used her social media platforms to distribute blatant lies and false information, amplified by multiple media outlets eager for the “rich socialite” morality tale. By the time jurors deliberated, Alexis’s testimony was no longer evidence, it was propaganda.

But now, thanks to Erickson’s sworn deposition taken on September 5, 2025, the record tells a different story. He was there and he admitted it under oath.

In his deposition, taken on September 5th, 2025, Erickson testified that he saw the two Iskander boys in the roadway seconds before the impact. He claimed that he passed them traveling between 45 and 50 miles per hour, looked back in his rearview mirror, and saw them still standing. He said there were no adults visible near the crosswalk. However, surveillance footage places Erickson’s vehicle in the same lane as Grossman’s just seconds after the crash, making his assertion that he somehow avoided striking the boys highly improbable.

After leaving the area, he went straight to Grossman’s home, where she called him at 7:11 p.m. saying, “I think something bad happened.” He then jogged back toward the scene, remained there for nearly three hours, and even made eye contact with Grossman as she stood near her vehicle surrounded by deputies.

He was not hiding. He was not invisible. He was right there, a key eyewitness, the driver of the car that passed the boys first, perhaps the last person to see the boys alive, the one whose presence could have introduced reasonable doubt.

The prosecutors knew it – and dismissed it.

Court records and attorney notes confirm the DA’s office located Erickson out of state and served him with a subpoena prior to Grossman’s trial. They knew his exact location. And they made the strategic choice not to call him to the stand.

The reason is obvious. Erickson’s testimony, though flawed, self-serving, and riddled with contradictions, would have blown a hole in the prosecution’s core theory. He wasn’t aligned with their “reckless socialite” narrative. He didn’t see Rebecca racing him down Triunfo Canyon. He didn’t see her hit the boys. His timeline didn’t fit theirs.

So they buried him. They erased him from the story and used his absence as a weapon against Rebecca’s daughter.

During his deposition, Erickson repeatedly invoked his Fifth Amendment right on questions about which of his two black Mercedes he was driving that night, a detail long suspected of tying him to the second vehicle seen on surveillance video. Yet, on nearly every other point, he answered, often inconsistently, but revealingly.

Those fragments were the direct forensic link that could have validated witness accounts of a second car. Their disappearance conveniently eliminated physical evidence that contradicted the prosecution’s single-driver theory.

And there’s more.

Erickson told investigators he was driving a different vehicle than he actually was that night. He then hid the real vehicle and tried to present authorities with the wrong car.

Former MLB player Royce Clayton, who spent the day drinking with Erickson before the crash, testified that Erickson made incriminating statements about the incident that effectively ended their friendship. Clayton’s testimony, combined with the missing vehicle evidence and Erickson’s own deceptive actions about his car, creates a picture so damning it’s impossible to ignore.

His statements suggest a man scrambling to save himself, twisting language to minimize culpability while inadvertently validating the defense’s theory that a second vehicle was involved.

Multiple attorneys present described Erickson’s testimony as “a minefield of self-preservation,” but even those evasions point to one unmistakable truth: he was physically present at the scene of the crash, a fact the prosecution fought to suppress because it shattered their narrative.

The Grossman prosecution wasn’t about justice; it was about branding. Castro and Gould needed a conviction that would rehabilitate Gascón’s image amid criticism that he was soft on crime. The death of two children presented the perfect “message case.” And Rebecca Grossman, wealthy, white, and married to a prominent surgeon, was the perfect foil.

The DA’s team had no interest in nuance. A complex accident involving multiple vehicles, obstructed sightlines, and questionable investigation tactics wouldn’t generate the outrage they needed. But a headline about a “drunk, speeding socialite who left two children to die” would.

To protect that narrative, they ridiculed witnesses, cherry-picked evidence, and buried the man whose testimony could have upended it all. The suppression wasn’t accidental, it was tactical.

In the months since the conviction, both Castro and Gould have appeared on panels, podcasts, and “justice reform” speaking circuits celebrating their win. They call the Grossman case a landmark, a victory for victims. What they never mention is that the victory came at the expense of truth.

By silencing Erickson, prosecutors not only misled the jury, they deceived the public. They knew a second driver existed. They had the subpoena to prove it. They chose not to ask him the one question that mattered: what did you see? Because they already knew the answer would unravel the story they had spent years selling.

Rebecca Grossman’s trial was a masterclass in narrative control, a performance masquerading as prosecution. Every witness was a prop, every omission a choice. And behind it all stood Scott Erickson, the man they swore wasn’t there, standing in plain sight the entire time.

The question now isn’t whether the DA’s office made mistakes. It’s whether those mistakes were deliberate, part of a larger culture within Los Angeles County justice where ambition eclipses ethics and winning replaces truth.

Rebecca Grossman wasn’t just convicted by a jury. She was convicted by a system that decided, long before the evidence was heard, that a headline mattered more than a human being.

And Scott Erickson, the missing witness they silenced, may ultimately prove what prosecutors fought so hard to hide: that the real deception began not on Triunfo Canyon, but inside the DA’s office itself.

DISCLAIMER: Investigative reporting in high-profile litigation cases published by The Current Report is non-commercial, fact-based journalism; any project fees compensate research and reporting labor only, sources participate solely in accuracy verification, and final publication is approved exclusively by The Current Report after fact-checking is confirmed.

Follow Us