Long Beach still remembers May 31, 2020. The looting, the fires, the National Guard, the chaos in every direction. While officers on the ground were fighting to regain control of a city in freefall, circling safely above it all in the Long Beach Police Department helicopter with a headset on and looking down from a protected aerial bubble, was then-Chief Robert Luna’s retired SWAT pal Robert Razo watching the city burn from hundreds of feet in the air at Luna’s direction while the rank-and-file fought for their lives below. The people who lived it still describe it the same way: cowardice with a rotor blade.

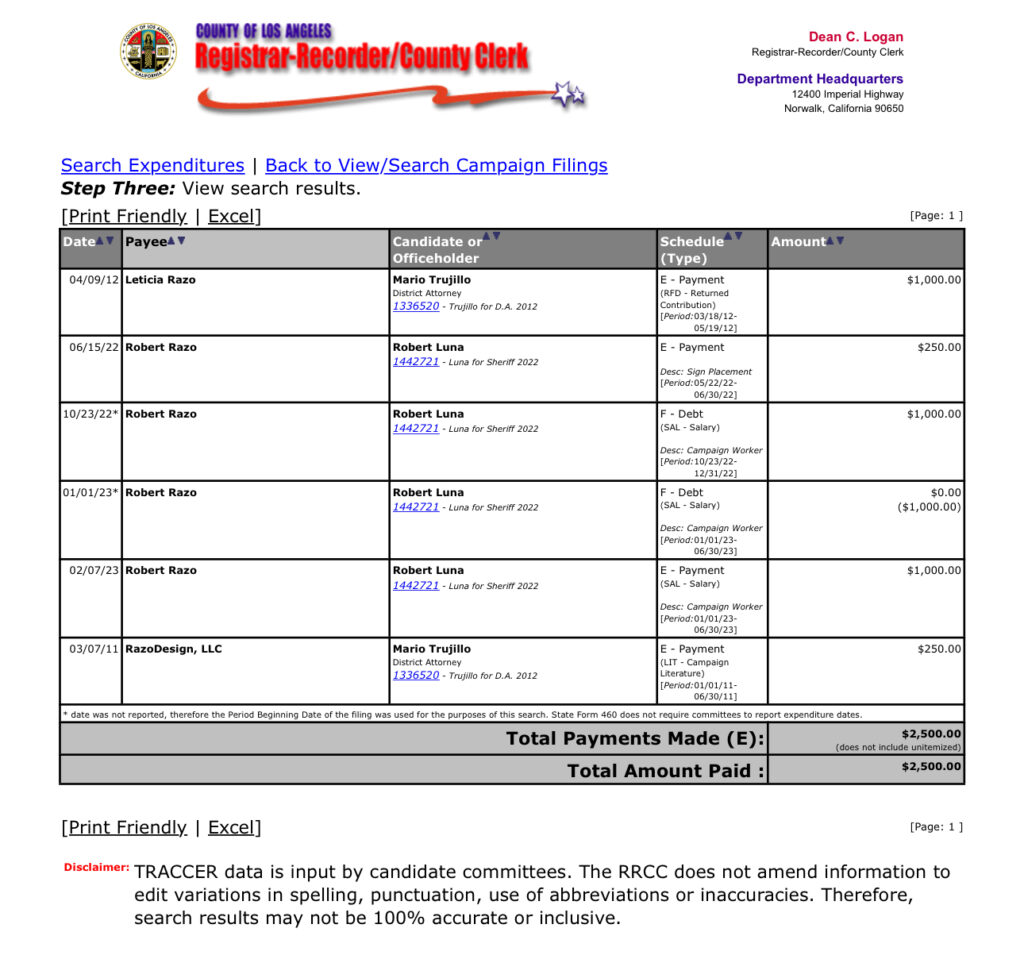

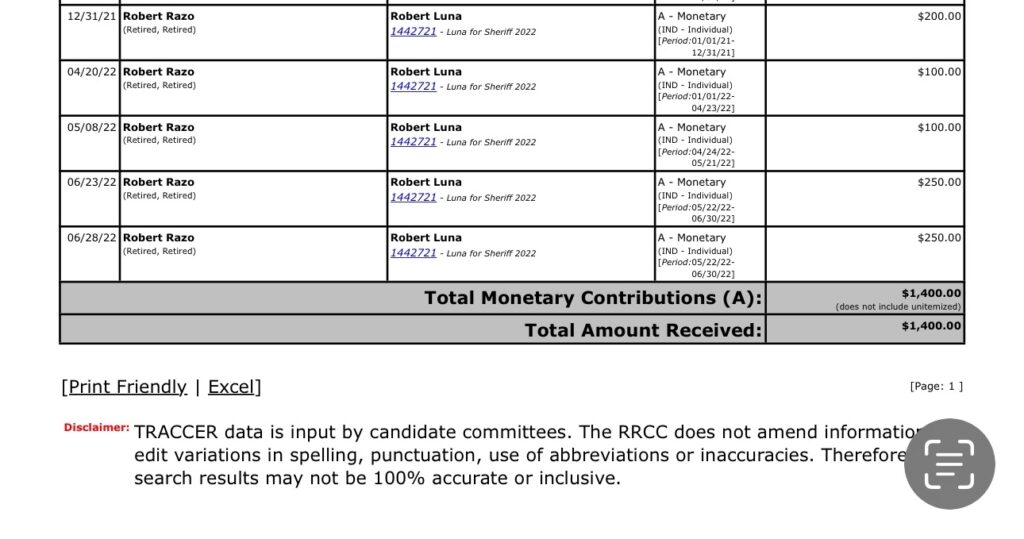

Fast-forward to 2022 and 2023, and suddenly Luna begins quietly paying that helicopter companion back. The campaign finance filings tell the story without editorializing. A small transaction in June 2022. Then an unusual entry just two weeks before the election: Luna’s campaign logs a one-thousand-dollar “debt” supposedly owed by Razo and described as salary for campaign work he never performed. On New Year’s Day, the debt vanishes, forgiven with the stroke of a pen. And then, two months after Luna is already sworn in as Sheriff, Razo receives a fresh one-thousand-dollar check labeled again as campaign worker salary. Post-election. Outside the legal window. A transparent payoff disguised as retroactive wages.

That is not clerical error. That is a direct violation of California law. Campaign funds cannot be used for personal benefit. Fake debts that are later forgiven are a known enforcement trigger. Post-election payments labeled as campaign activity are prohibited. The FPPC has fined Herb Wesson, Curren Price, and George Gascón’s teams for these similar payments. Luna’s version is even more blatant because the timeline and labeling do not match reality. There was no campaign work. There was reward.

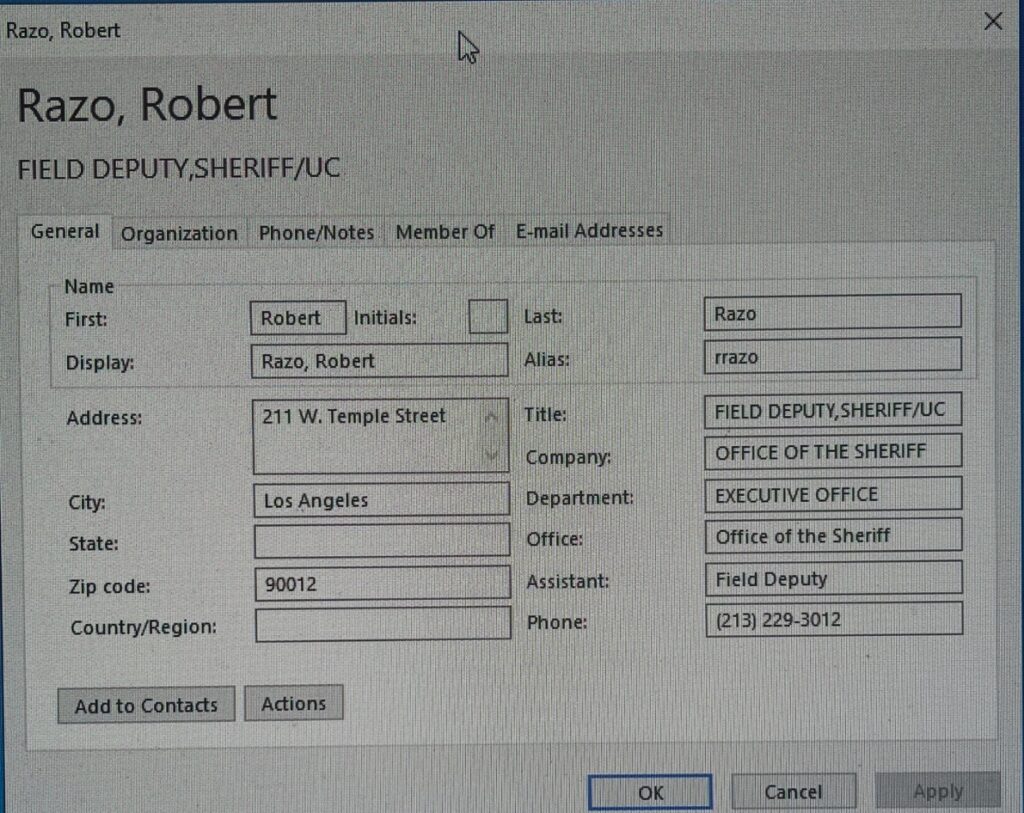

And the true payoff wasn’t the money. It was power. Immediately after Luna was sworn in, Razo materialized inside LASD as something far more influential than a retiree with a title. Insiders from multiple divisions confirm the same disturbing truth: Razo is effectively the second-in-command of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. No badge says undersheriff, but he acts like one. He chaired Luna’s transition team. He handpicked assignments. He directed promotions. His signature moved people into positions of power long before Luna had even memorized the layout of the eighth floor. Every major personnel decision under Luna’s first year has Razo’s fingerprints all over it. An unelected, unvetted, unaccountable shadow executive controlling the largest sheriff’s department in the nation.

Two beneficiaries stand above the rest. Jason Skeen and Nancy Escobedo, both loyal to former Sheriff Jim McDonnell, were ushered into prime positions almost immediately. Skeen’s story is the most revealing. While still on Sheriff Alex Villanueva’s command staff, Skeen was quietly feeding confidential personnel information, internal strategy, and lists of Villanueva supporters directly to Luna’s team. Deputies loyal to the sitting sheriff suddenly found themselves shipped to remote assignments, boxed out of promotions, or buried in administrative backwaters. The pattern didn’t come from guesswork. It came from Skeen’s betrayal.

His reward was meteoric. The moment Luna took office, Skeen was elevated to Chief, then to Assistant Sheriff, and insiders say the plan is already in motion to make him the next Undersheriff once April Tardy is pushed out. From trusted insider to department traitor to the second most powerful person in LASD in under two years. Escobedo received her own high-profile landing spot, similarly padded, similarly unquestioned.

This isn’t reform. This is a loyalty bonus system wrapped in the language of progress. Illegal campaign cash converted into post-election favors. Helicopter companions transformed into shadow commanders. Department turncoats rewarded with promotions and authority they could never have earned on merit. Luna didn’t dismantle corruption; he imported McDonnell’s old guard, repackaged it, and paid for it with money he was never allowed to spend.

If this were happening under Alex Villanueva, the Los Angeles Times would be running front-page exposés, day after day, demanding accountability and state intervention. Because it’s Luna, the so-called reformer, the silence is thunderous.

Sheriff Luna, the public deserves the truth: What was that February one-thousand-dollar payment really for? Campaign work that never happened, or the first installment of what you owed the man who now runs your department from the shadows while your Benedict Arnold collects his reward on the eighth floor?

The FPPC will be asking the same question, and they’ll be doing it with subpoena power.

The blades that kept Luna safe on May 31, 2020 are still spinning, and the trail of money and promotions is getting hotter by the day.

If you believe Sheriff Luna and his campaign violated California campaign finance laws with that post-election payment to Razo, you can file a complaint with the Fair Political Practices Commission anonymously. The FPPC’s electronic system is functioning even if it displays a temporary error. One submission is enough to trigger a formal review. The rank-and-file who were left choking on smoke while others watched from above deserve that accountability.

Let your voice be heard.

Follow Us