*Featured photo source: Facebook

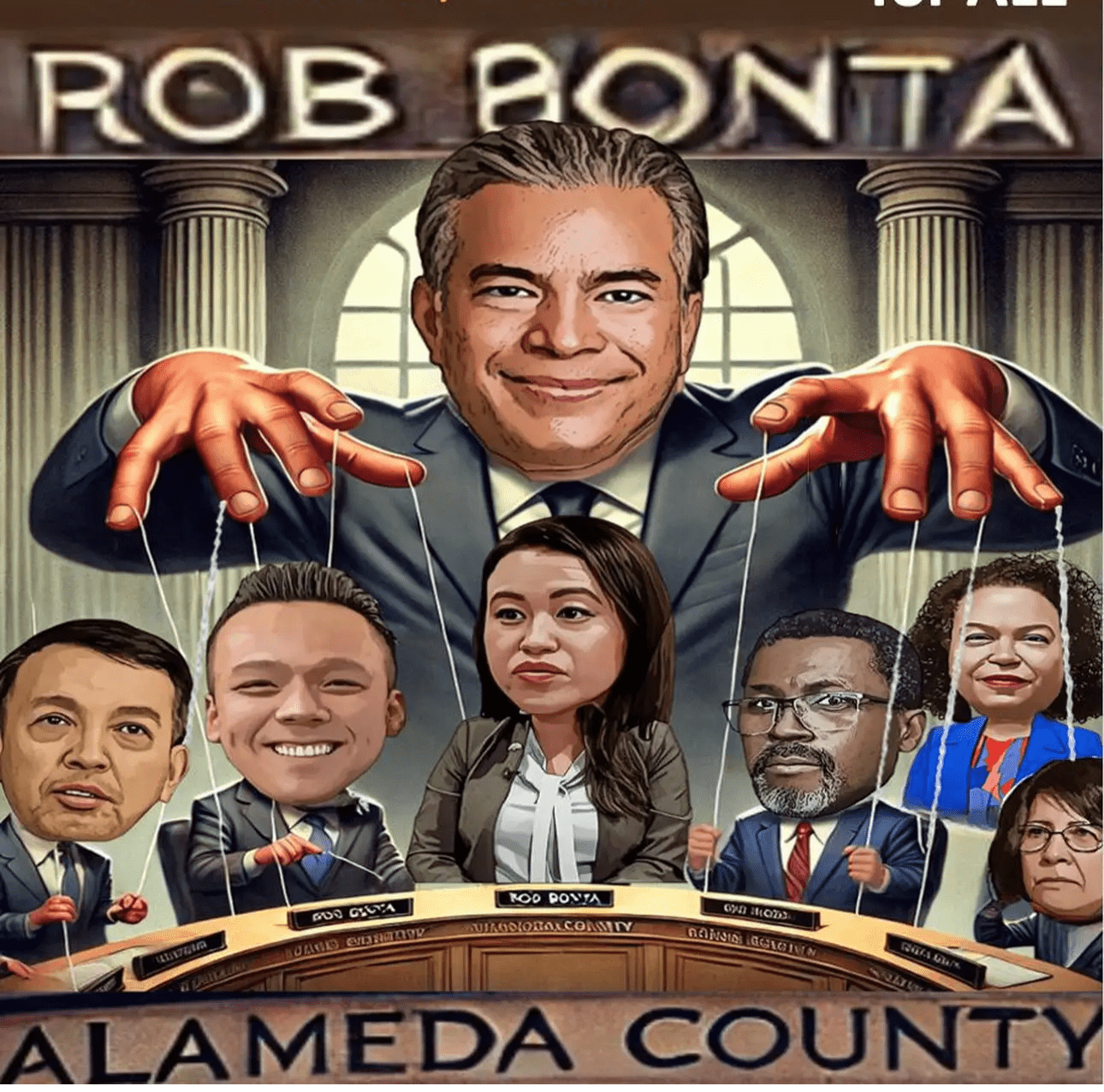

Deep inside California’s political underworld, where public servants morph into power brokers and the rules flex for those with the right connections, another ethics firestorm is igniting. At the center is California Attorney General Rob Bonta, the man sworn to uphold the law while now raising serious questions about how faithfully he follows it himself.

New filings reveal Bonta quietly siphoned off nearly half a million dollars in campaign funds, $468,000 and counting, to pay Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, a heavyweight law firm representing him in a federal bribery investigation engulfing the East Bay political machine. Bonta insists he’s simply a “witness.” But federal investigators, a mysterious “compromising” video, and Bonta’s increasingly panicked legal spending tell a far murkier tale.

This scandal surfaced when political watchdog Raphael Rothschild filed a formal complaint with the Fair Political Practices Commission (FPPC), alleging Bonta violated the Political Reform Act by using campaign funds for what looks suspiciously like personal legal protection. The investigation revolves around the Duong family, the influential Cal Waste Solutions owners indicted for engineering straw donations and bribing local officials, and former Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao, recalled after federal agents raided her home. The Duongs allegedly bought political access. Thao allegedly delivered favors. And Rob Bonta? He’s somewhere in the middle of this mess, wrapped in enough legal insulation to bankrupt a small campaign.

Bonta’s team calls the complaint “silly.” But nothing about a half-million-dollar donor-funded legal war chest screams innocence. Add the revelation that one of the defendants allegedly captured a “compromising” video of Bonta, and suddenly this looks less like routine witness representation and more like a preemptive containment strategy. If Bonta has nothing to hide, why deploy some of the most expensive lawyers in the country? Why use donor funds intended for elections, not personal reputation management? And why not use state resources if this truly relates to his role as Attorney General?

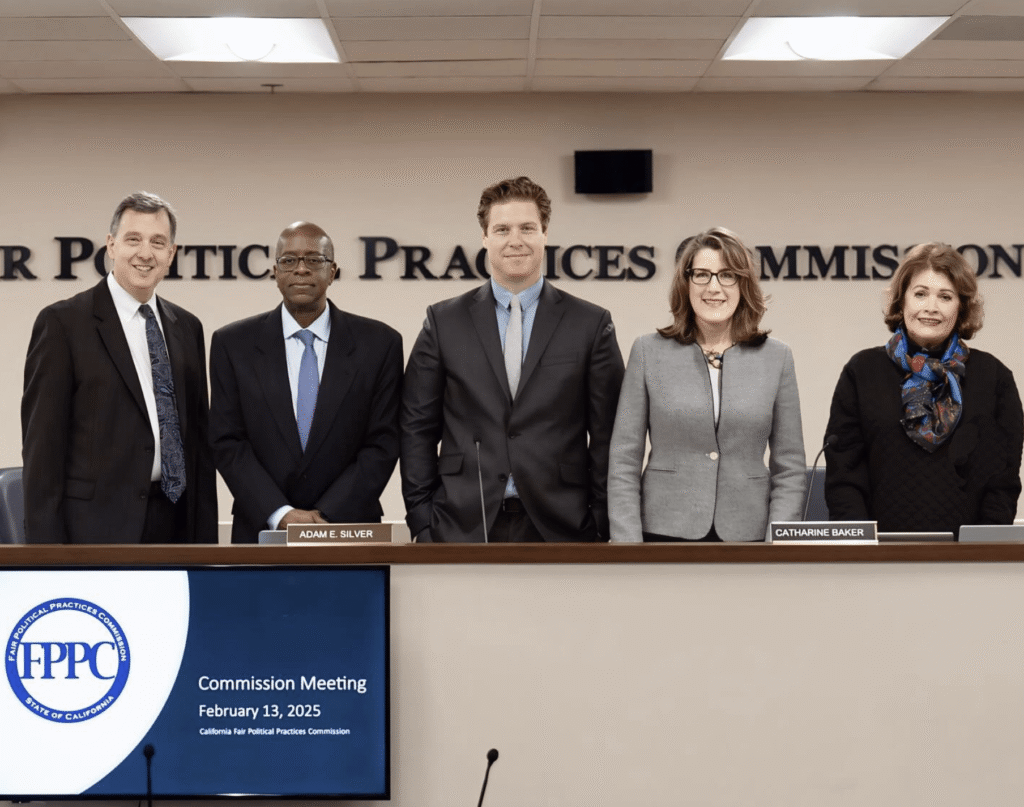

The FPPC acknowledged the complaint on November 19th and promised a decision within 14 days. That deadline blew by without action. On December 10th, the commission sheepishly admitted it “needed more time.” No explanation. No timeline. No transparency. Just another opaque delay from an oversight body with a long history of dragging its feet when powerful officials are involved.

And in this case, the conflict of interest is baked into the system.

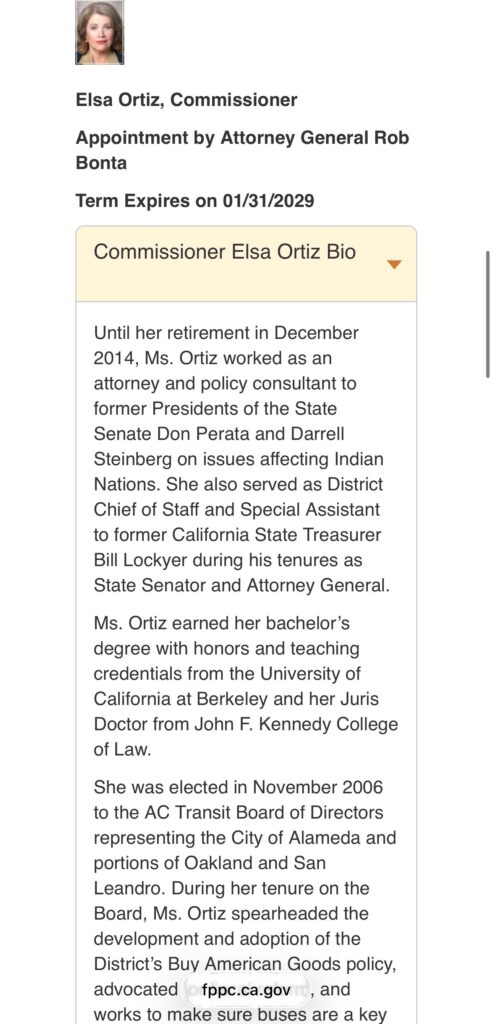

The FPPC’s five commissioners are appointed by the very politicians they’re supposed to police. In Bonta’s case, that includes one of his own appointees: Commissioner Elsa Ortiz, a longtime East Bay political insider Bonta selected in 2023. Ortiz’s term runs through 2029, meaning she will directly weigh complaints involving the man who put her in the job. That alone should disqualify the FPPC from touching this case. But the web gets thicker.

Ortiz and Bonta hail from the same East Bay political machine, a tight, insular universe where insiders rotate through staff jobs, consultant gigs, and “public service” roles like pieces on a chessboard. Ortiz spent decades intertwined with Democratic power circles, including working for former AG Bill Lockyer, Bonta’s predecessor and a defining force in the region’s political landscape. She served on AC Transit’s board for more than a decade, representing areas overlapping Bonta’s old Assembly district. She championed transit policies Bonta legislatively amplified, including a 2020 Bay Bridge bus lane initiative where their collaboration was explicit. They’ve appeared together on endorsement slates for candidates like Liz Ortega for Assembly and Phong La for Alameda County Assessor. Ortiz’s committee even donated to Bonta’s first Assembly run in 2012. Small money, big signal: team loyalty.

Individually, none of these connections prove wrongdoing. Collectively, they form a portrait of an oversight commissioner deeply embedded in the political orbit of the man under scrutiny. It’s the classic California problem: the watchdog shares a kennel with the wolf.

Meanwhile, Bonta is quietly positioning himself for a 2026 gubernatorial campaign. The last thing he needs is a federal bribery probe, even one where he claims to be a witness, colliding with his donor-funded legal spending, his East Bay alliances, and a “compromising” tape floating around the evidence pool. The optics alone could derail a statewide run.

But optics are only part of the problem.

California law allows campaign funds to pay for legal expenses tied to political, legislative, or governmental duties, not for personal matters, personal benefit, damage control, or legal predicaments that fall outside the scope of officeholding. If the FPPC finds Bonta misused campaign funds, penalties could include significant fines, repayment, and far-reaching political consequences.

Yet the FPPC has a track record of slow-walking investigations involving high-ranking officials, sometimes allowing them to win elections before accountability lands. And now, with a commissioner directly appointed by Bonta voting on whether to investigate him, the credibility of the oversight process is already in question.

This case is unlike previous FPPC actions involving misuse of funds, cases that have involved mayors, supervisors, or political committees misallocating campaign resources for vacations, meals, personal bills, and unrelated legal costs. Those mattered, but none involved the state’s attorney general employing some of the most expensive lawyers in the country, in a federal corruption probe with personal undertones, while simultaneously preparing a run for governor. And none involved a situation where the accused official directly appointed one of the commissioners reviewing the complaint.

To understand just how far outside the norm Rob Bonta’s situation veers, it’s worth looking at how the FPPC has handled similar cases in the past. The commission has a long history of wrestling with complaints involving politicians who dip into campaign coffers for legal fees or personal perks that clearly fall into the forbidden “personal use” category. Time and again, the FPPC has issued fines or settlements, but the real pattern is the slow-motion pace of enforcement – a system that often protects the powerful by simply running out the clock.

In 2018, several FPPC cases again highlighted misuse of funds, including one committee reprimanded for spending money on legal fees wholly unrelated to campaign activities. The outcomes were predictable: stipulated agreements, penalties, and the familiar sense that California’s political watchdog barks loudly but bites softly.

In 2020, the FPPC leveled a $1.35 million penalty against the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors for violating campaign finance laws tied to a pay-to-play scheme. Even with the magnitude of that scandal, the case only concluded after years of investigation, underscoring the commission’s reputation for marathon-length probes.

A few years earlier, Menifee Mayor Scott Mann quietly settled with the FPPC after using donor money on family trips, meals, and other personal expenses. The commission ordered fines and repayment, reiterating that campaign funds must be tethered to legitimate political purposes – a standard that cuts straight to the heart of the Bonta complaint.

A 2024 CalMatters investigation laid the pattern bare. The FPPC often takes years to resolve complaints, sometimes allowing politicians to glide through entire election cycles before accountability catches up, if it ever does. One probe into a powerful donor network stretching back to 2022 remains unresolved amid allegations of improper contributions, a glaring example of delays that serve political interests more than the public.

Legally, the rules are straightforward. Campaign funds may cover legal fees only when tied directly to allegations involving elections, political activity, disclosure laws, or duties connected to holding office. Personal benefits, anything that supports an official in their private capacity, are strictly off-limits. And when civil or criminal matters fall outside those boundaries, politicians must create separate legal defense funds with their own disclosure requirements.

That’s the framework every California elected official is supposed to follow. Bonta’s half-million-dollar detour through campaign accounts tests those boundaries in ways that should alarm anyone watching the state’s top law enforcer blur the line between political necessity and personal protection.

In the state with the largest political war chests in America, campaign accounts frequently morph into slush funds for the powerful. But when the state’s top law enforcer dips into his donor pool to shield himself from federal fallout, not official duties, the public deserves more than obfuscation and delays.

Bonta promised transparency. Instead, Californians get half-million-dollar legal bills, federal agents probing political favors, an unexplained video, a watchdog possibly compromised by allegiance, and a campaign machine spinning overtime to deny the obvious: something here stinks.

Whether the FPPC acts or continues its time-honored tradition of protecting the well-connected will reveal more about the state of California democracy than any press release from the Attorney General’s office ever could. Because if Rob Bonta can redirect donor cash to insulate himself in a federal corruption scandal, and a commissioner he appointed helps decide whether that’s acceptable, then the system isn’t just broken.

It’s rigged.