As if the political climate weren’t already toxic enough, no one should be surprised that inside Los Angeles County’s Hall of Administration, oversight is only tolerated when it serves political interests.

The sudden retirement of Inspector General Max Huntsman has ignited a firestorm just beneath the surface. On December 9, 2025, Max Huntsman, the longtime Inspector General charged with scrutinizing the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, announced he was retiring after 12 years in the role. The Los Angeles Times dutifully cast the exit as a graceful farewell, spotlighting Huntsman’s open letter criticizing the county’s half-hearted reform efforts and highlighting his office’s exposés on jail conditions, deputy gangs, and systemic failures. But sources inside the Hall of Administration and deep within LASD paint a much darker picture, one rooted in calculated retaliation, internal warfare, and a deliberate push to silence the last remaining critics willing to challenge Sheriff Robert Luna’s administration.

Huntsman’s exit is not an isolated event. It is the latest chapter in a pattern in which key oversight figures, Sean Kennedy, Robert Bonner, and now Huntsman himself, have been pushed out, neutralized, or outright silenced. And at the center of this purge sits the county’s most politically potent narrative: deputy gangs. It was the storyline that helped bring down former Sheriff Alex Villanueva in 2022, a cudgel wielded aggressively by a Board of Supervisors dominated by Democratic allies who wanted him gone. But with Luna—the board’s preferred successor—now occupying the sheriff’s seat, that same narrative became a liability. Suddenly the very weapon they once used to dismantle Villanueva threatened to splash mud on their ” puppet” successor. “The board’s loyalty to Luna runs deeper than their tolerance for bad press,” a department source revealed. “Huntsman and the COC were getting too loud, and they had to go.”

Huntsman had been a thorn in LASD’s side from day one. Since his appointment in 2013, he issued blistering reports on alleged deputy gangs, those secretive, tattooed internal cliques long accused of excessive force, misconduct, and toxic influence over department culture. In February 2024, his office went even further, urging the county to disband the LASD’s Risk Management Bureau, labeling it “aggressive” and corrupt for shielding high-ranking officials while retaliating against whistleblowers.

Luna, who campaigned on eradicating deputy gangs, quickly found himself in the crosshairs. In September 2024, Huntsman blasted Luna’s new anti-gang policy, calling it toothless and insisting in an LAist interview that it wouldn’t come close to cracking the department’s entrenched “50-year code of silence.” He revealed that his office had been excluded from the policy’s development altogether, despite Luna publicly claiming otherwise. Civilian Oversight Commission Vice Chair Hans Johnson attempted to soften the blow by calling the policy “progress,” but even he admitted it lacked the force necessary to break up deeply rooted groups.

That public clash set off alarm bells for the Board of Supervisors that they themselves could not identify. They had weaponized the alleged deputy gang narrative successfully against Villanueva, painting him as an enabler of internal corruption. But now Luna was facing similar questions, deputies with tattoos in executive ranks, stalled investigations, sluggish reform. The board feared a repeat of 2022. “They knew how powerful the narrative was against Villanueva,” another Hall of Administration source told me. “They couldn’t let the same thing stick to Luna. Huntsman, Kennedy, Bonner, they were all calling him out. The board lost control.”

The purge began with Civilian Oversight Commission member and former chair Sean Kennedy. In February 2025, Kennedy resigned in protest, citing interference from county lawyers. The breaking point was the Commission’s attempt to file a legal brief supporting former prosecutor Diana Teran, who had been charged with hacking after sharing deputy misconduct records. County Counsel blocked the filing, insisting that the Board of Supervisors approve it, an unprecedented move Kennedy said undermined the COC’s independence. In his resignation letter, he accused the county of using the Teran case as a pretext to withhold key documents on shootings, beatings, and alleged deputy gang activity.

Four months later, in June 2025, COC Chair and former federal judge Robert Bonner was pushed out. In a letter to Supervisor Kathryn Barger, Bonner expressed frustration at being replaced mid-term, even as he was spearheading transparency reforms under AB 847, legislation allowing oversight bodies to review confidential documents in closed sessions. Bonner had also been pursuing changes to county code to strengthen the COC’s independence. Barger’s office dismissed the timing as a need for “new perspectives.” Bonner called it what it was: retaliation for publicly criticizing Luna’s slow progress on alleged deputy gang reforms.

By September 2025, the county escalated the crackdown. A new communications policy required oversight officials to route every press release, public statement, even outreach to individual supervisors, through the Executive Office for “review, approval, and coordination.” Oversight leaders condemned the policy as a gag order. At a COC meeting, incoming chair Hans Johnson called it “caustic, corrosive, and chilling,” making clear the Commission would not be muzzled. Yet this new policy, crafted by communications manager Michael Kapp, was conveniently framed as ensuring “alignment.” Critics like the ACLU’s Peter Eliasberg called out the obvious: the policy existed to tamp down reports on jail horrors, vermin, spoiled food, preventable inmate deaths, that embarrassed Luna’s administration.

While the Board was tightening its grip politically, Luna was fighting his own war behind the scenes. Sources say constitutional policing advisor Director Eileen Decker, a former U.S. Attorney and one of Luna’s most powerful strategists, worked hand-in-glove with the sheriff to orchestrate Huntsman’s downfall. Publicly, Luna praised oversight and embraced reform. Privately, he worked to undermine the very office tasked with holding him accountable. “Luna was losing deputy support,” a Sheriff’s Department insider revealed. “Executives with tattoos felt targeted, and he needed to show he wasn’t Villanueva 2.0. But he couldn’t openly attack oversight. So he used proxies.”

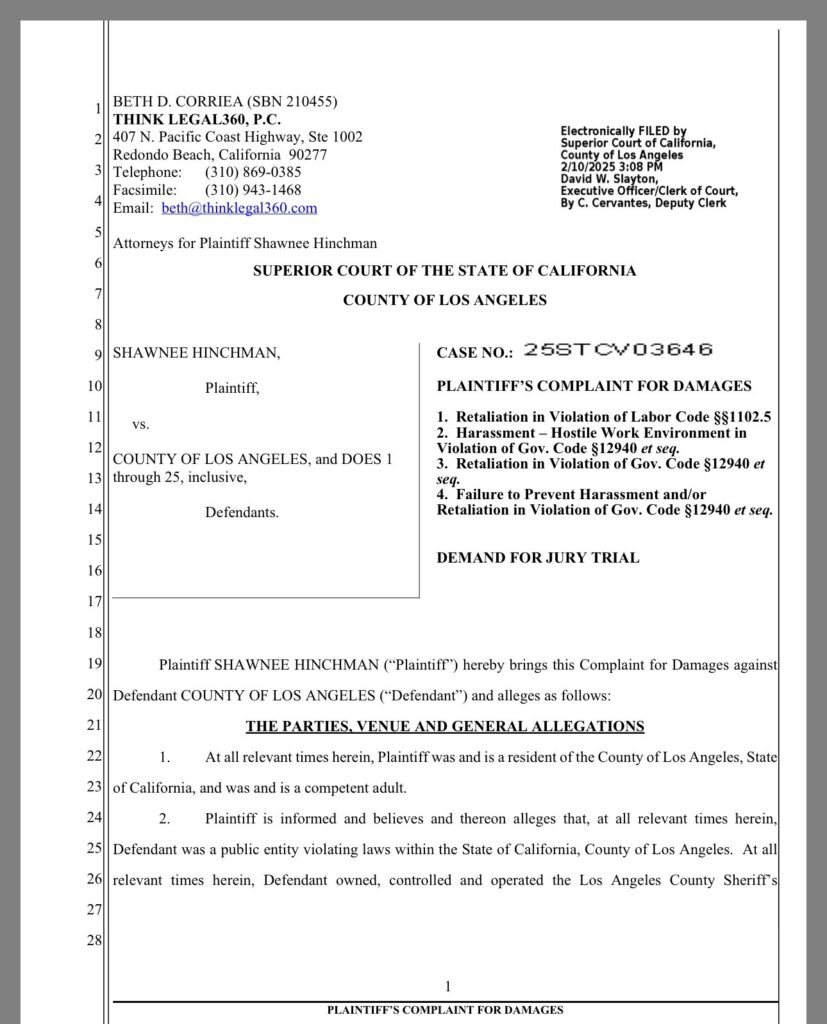

One of those proxies, according to multiple sources, was Captain Shawnee Hinchman. In February 2025, Hinchman filed a sweeping lawsuit against L.A. County alleging whistleblower retaliation, harassment, and a hostile work environment under Government Code sections §1102.5 and §12940. Her complaint laid out a detailed timeline: her promotion to captain of the Risk Management Bureau in March 2022; repeated reports to Commander Rodney Moore and Decker about internal misconduct; charged interactions with Huntsman, whom she accused of improper disclosures to POST and harassment; and her 2024 demotion and denial of promotions she said she was qualified for.

In the lawsuit, Hinchman claimed Huntsman orchestrated “a campaign of harassment, bullying, intimidation, and/or retaliation,” including false accusations of dishonesty under Penal Code §13510.8. She said Decker told her Huntsman believed she was a “deputy gang associate” and that his push to dismantle the RMB was really about punishing whistleblowers. Hinchman is seeking damages for lost wages, emotional distress, and attorneys’ fees.

But the lawsuit was only the opening move. According to insiders, Luna and Decker not only encouraged Hinchman’s suit, they actively recruited other women in the department to file similar claims, building a coordinated effort to discredit Huntsman and undermine his authority. “They played chess while everyone else played checkers,” one source said. “Once the lawsuits were lined up, the board had all the cover they needed. Huntsman was done. And the whole time, Luna kept pretending he was welcoming oversight.”

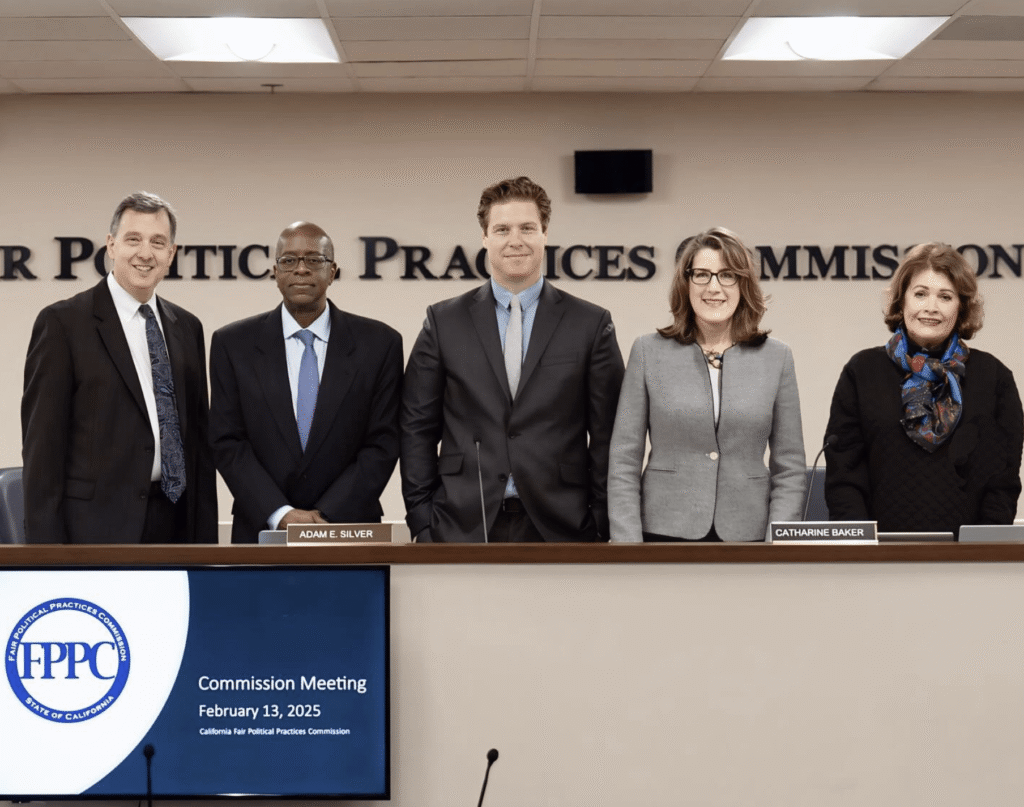

The finishing blow came when the Board of Supervisors, quietly and without fanfare, retained former U.S. Attorney’s Office Criminal Chief Mack E. Jenkins, now a partner at Hecker Fink LLP, to investigate Huntsman. Jenkins is known for prosecuting L.A. political heavyweights like José Huizar and Mark Ridley-Thomas, cases intertwined with the same political network backing Luna. Critics immediately recognized the move for what it was: an “internal” probe designed to apply pressure, not uncover truth.

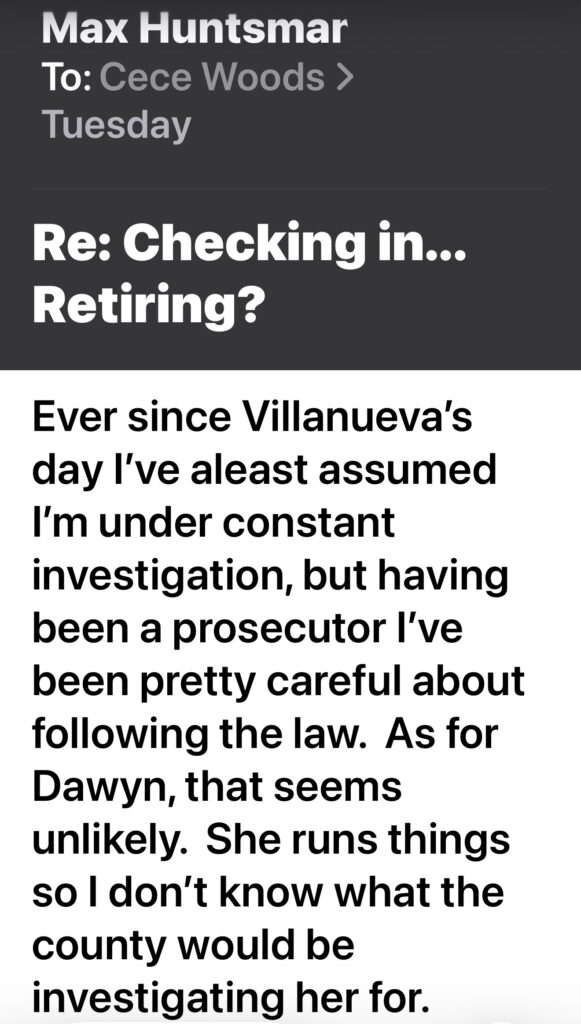

Why retire now? According to sources, Huntsman stepped down to avoid being dragged into a politically charged investigation he knew was not operating in good faith. In an email responding to questions about the probe around the time of his announcement, Huntsman didn’t deny it existed. Instead, he wrote, “Ever since Villanueva’s day I’ve at least assumed I’m under constant investigation, but having been a prosecutor I’ve been pretty careful about following the law. As for Dawyn, that seems unlikely. She runs things so I don’t know what the county would be investigating her for.”

His open letter lamented ignored reforms, but the circumstances around his retirement reek of coercion. The Board declined to comment. Luna’s office declined to comment. And yet the pattern is unmistakable: in Los Angeles County, critics of the status quo are disposable the moment they threaten those in power.