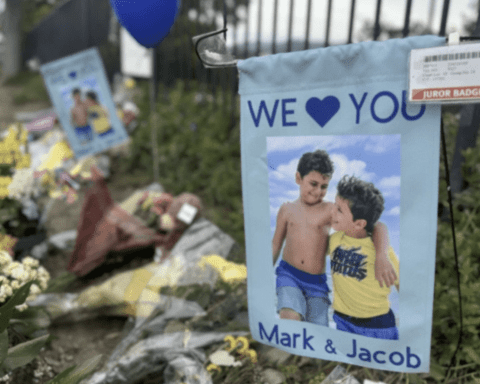

They built the Rebecca Grossman case the way LA County builds most politically convenient prosecutions: choose the villain first, then build the investigation around that conclusion until the paperwork looks like proof. The public was fed a simple story because simple stories sell, and because complexity is dangerous when it threatens a conviction. But this crash was never a one-car event, and Grossman was never the only driver whose actions mattered. There was another vehicle in the same lane in front of Grossman, and another chain of decisions unfolding seconds ahead of the defendant’s Mercedes. His name is Scott Erickson, and the most unsettling question in this entire case isn’t what he did. It’s why the justice system acted like it couldn’t afford to find out.

This case has always had a second driver. A second vehicle. A second set of hands on the wheel moving at speed through that same dark stretch of roadway seconds before impact. A man whose name should have been central to any honest investigation but instead became the system’s most protected variable.

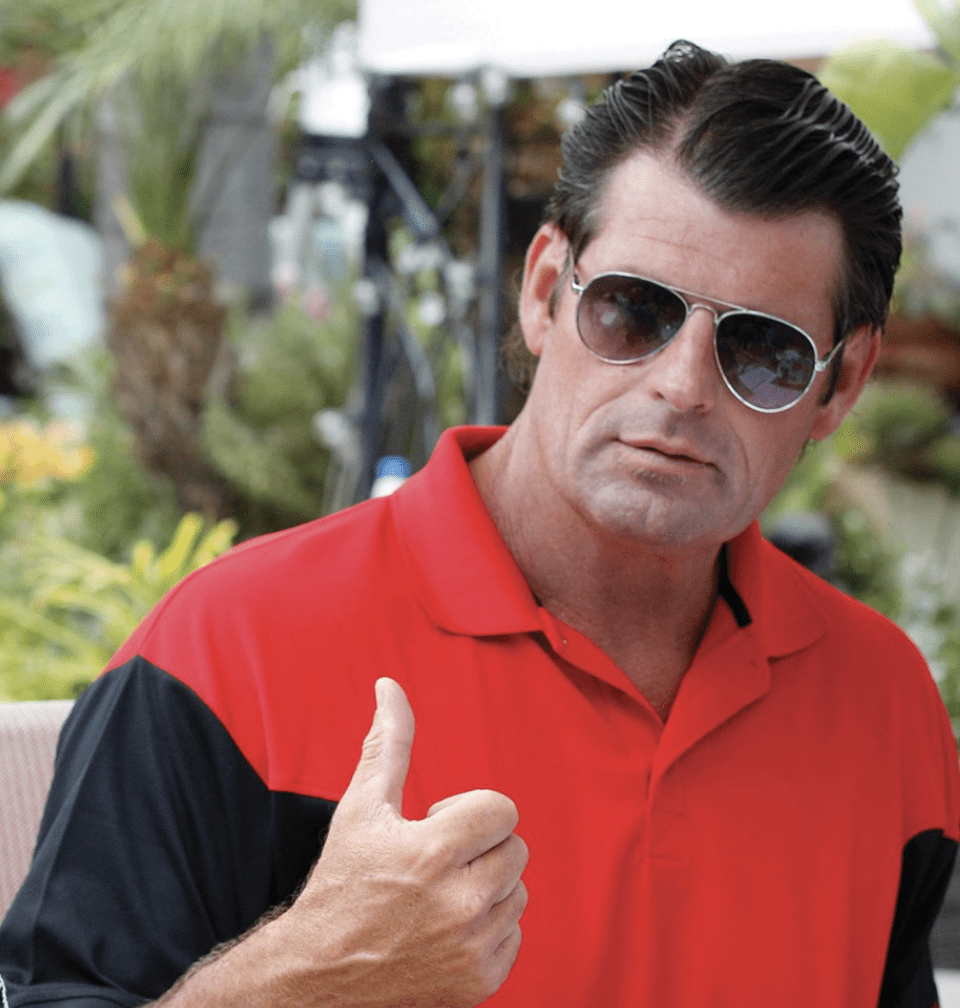

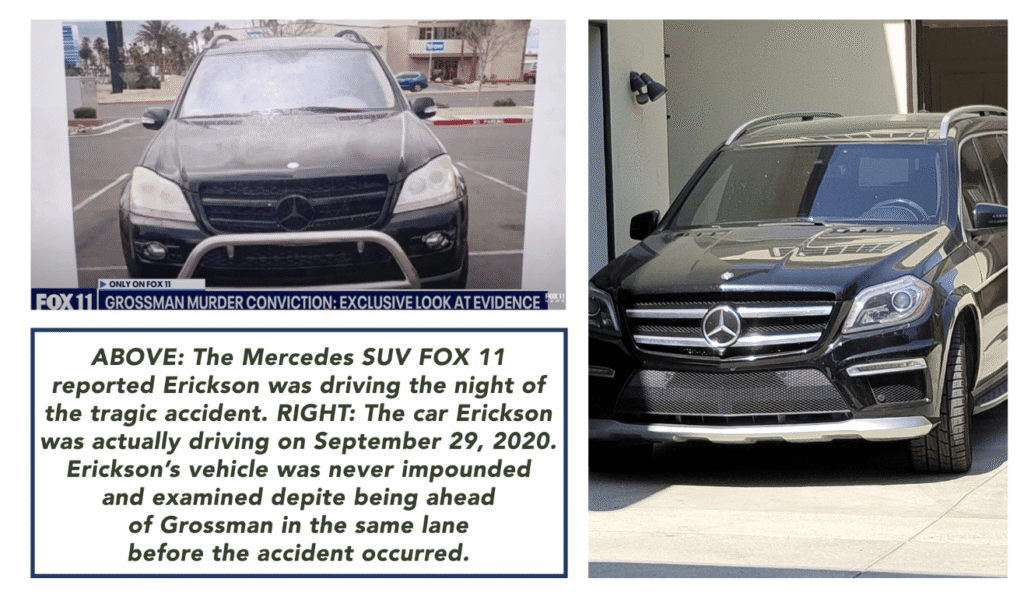

Scott Erickson was not a bystander. He was not a neutral witness. He was not incidental to the chain of events. He was the person Grossman was behind. He was the driver in the black SUV that appears on surveillance footage just ahead of her in the No. 2 lane. He was part of the pack of speeders witnesses described. He was the one who left, then returned, then left again without identifying himself as the driver directly in front of the defendant when two children were struck.

And for reasons that do not withstand scrutiny, law enforcement and prosecutors treated him as untouchable.

The public was asked to accept a single-cause tragedy. Grossman hit the children. Grossman caused the debris. Grossman caused both impacts. Grossman bears total responsibility. But that certainty was not earned through a comprehensive forensic investigation. It was manufactured by narrowing the investigation until it could only produce one answer.

The second vehicle theory is not a defense fantasy. It is stitched into the timeline and supported by witness accounts and evidence entries that were either ignored or allowed to disappear. Witnesses described hearing two separate impacts, spaced roughly three to five seconds apart. That timing matters because the surveillance evidence placed Erickson’s SUV in front of Grossman’s Mercedes by approximately three seconds in the same lane. In other words, the spacing between Erickson and Grossman matches the spacing between the reported impacts.

That is not coincidence. That is sequence.

If Erickson’s SUV struck first, or if it clipped one of the children, or if it triggered the initial collision dynamic that forced bodies into Grossman’s path, then criminal causation becomes far more complex than the prosecution wanted jurors to consider. That is why Erickson’s presence is so dangerous to the state’s theory. It injects reasonable doubt at the precise point prosecutors needed certainty most.

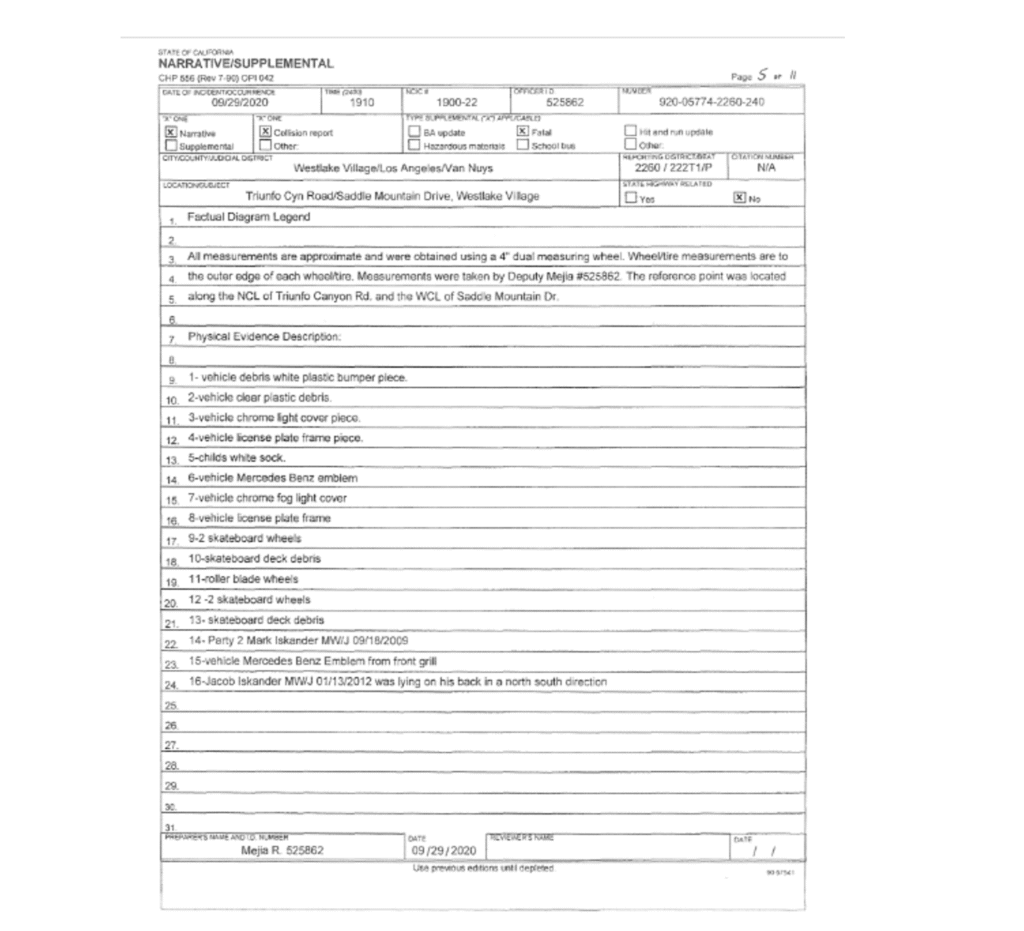

Then comes the debris, the kind of evidence that should have set off alarms inside any competent investigative team. The evidence log from the scene included a chrome fog light cover and a license plate frame, items that did not align with Grossman’s Mercedes. Grossman’s vehicle did not have fog lights. Erickson’s Mercedes SUV models did. Those items were entered into the record and then vanished from the evidentiary chain, never meaningfully appearing in later reports in the way they should have if the investigation had been conducted like a homicide-level traffic case. Evidence does not simply evaporate in serious cases unless it is mishandled, unprotected, or inconvenient.

Even more disturbing than what was logged is what was never done.

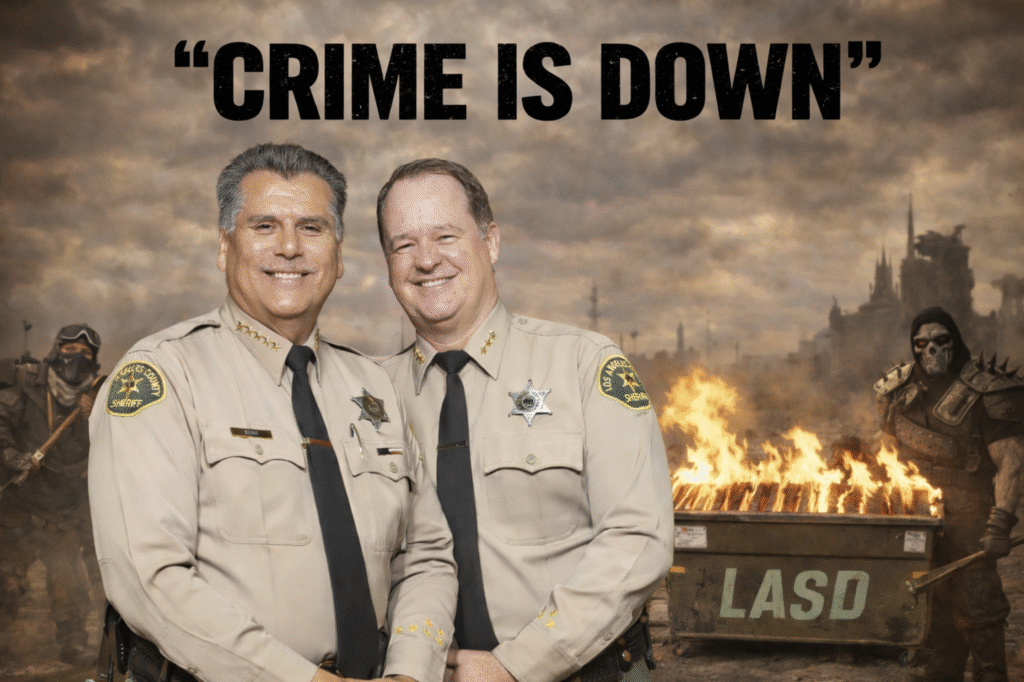

Erickson’s vehicle, the vehicle that matters most if you care about truth, was never impounded. It was never forensically examined. No documented inspection. No collision reconstruction tied to his front end. No photographed damage analysis. No measurement of height-to-impact alignment. No forensic testing for paint transfer or biological material. No serious effort to preserve the one piece of physical evidence that could confirm or obliterate the second vehicle theory.

The lead SUV was treated like it was exempt from investigation, as if the entire justice system silently agreed it was better not to know.

The sworn testimony later reflected that reality. Detective Huelsen acknowledged that neither he nor anyone else examined or impounded Erickson’s SUV. Officers supposedly went to Grossman’s home looking for Erickson’s vehicle, yet no credible record exists of the vehicle being secured, photographed, or inspected. That failure does not read as oversight. It reads as deliberate omission, because no investigator in a fatal child collision forgets to examine the lead vehicle unless they have decided the lead vehicle cannot become a problem.

Erickson’s own behavior that night makes it even harder to believe he was treated as irrelevant by accident.

He did not stop at the scene. He kept driving. Later he returned and lingered near the crash site, blending into the crowd while deputies worked the aftermath, yet he did not identify himself as the driver who had been directly ahead of the defendant. He did not make himself available for scrutiny. He did not step forward and demand to give a statement. He did what people do when they are trying to manage exposure. He observed. He controlled. He disappeared.

Then comes the most damning detail, the kind that makes an investigator’s spine tighten because it sounds like the language of concealment, not innocence. Erickson allegedly interacted with Grossman’s daughter near the scene and asked, “Why did she stop?” followed by a chilling directive: “You never saw me here.” Those are not the words of a man with nothing to hide. Those are the words of a man attempting to erase his presence while a crime scene is still hot.

And while the public was expected to believe he was merely a companion who happened to be nearby, Erickson’s next move was not what innocent witnesses do. He met with high-profile defense attorney Frankie Longo the very night of the crash. Most people do not consult counsel within hours of a collision involving dead children unless they believe they are at legal risk. It signals fear. It signals liability. It signals a consciousness that the truth, if pursued honestly, would be dangerous.

The vehicle issue grows even darker when you account for the two-SUV discrepancy. Erickson owned two black Mercedes SUVs, including a 2007 ML450 with a front metal bumper guard and a 2016 GLC63 AMG. Erickson reportedly represented to authorities that he was driving one vehicle that night, while later reporting indicates he was actually driving the other. If he lied about which SUV he drove, then the reason is obvious. He wanted to steer investigators away from a vehicle that could contain evidence.

In a legitimate investigation, that discrepancy alone would trigger immediate impound and inspection of both vehicles, with paint transfer tests, front-end damage analysis, and full photographic documentation. That did not happen. The system allowed Erickson to control what the record became, instead of forcing the record to control him.

Other pieces of the timeline deepen the suspicion. Erickson reportedly contacted Royce Clayton after the crash, telling him what happened and warning him not to come to Grossman’s home. Clayton’s involvement matters because he had been with Grossman and Erickson earlier in the evening at Julio’s restaurant before separating from them. The night was not a mystery. The drinking and movement of the group could have been mapped, verified, timed, and tested. But what emerged instead is a sense that the only goal was to lock onto Grossman and make the second driver disappear from meaningful forensic attention.

Then comes the surveillance evidence disaster, a detail that makes this case look less like procedural failure and more like evidentiary sabotage. Sergeants Scott Shean and Travis Kelly reviewed surveillance footage from local sources the day after the crash, footage that allegedly captured multiple vehicles and reinforced the existence of the high-speed convoy. Instead of properly seizing, preserving, and cataloging the footage, it was recorded on personal cell phones. The original files were not adequately protected and were ultimately lost. This isn’t a minor technical lapse. When the timeline and vehicle sequence are the core truth of the case, mishandling surveillance is not a paperwork issue. It is the destruction of objectivity.

The next 48 hours became the point of no return.

The most critical window in any fatal collision investigation is the first two days. That is when vehicles still have unaltered evidence. That is when damage patterns are fresh and measurable. That is when debris fields still tell the truth. That is when you secure the physical facts before narratives calcify.

But instead of doing that, the investigation hardened into a conclusion before evidence could challenge it.

According to reporting, Scott Butler, a retired LASD detective and cousin to Royce Clayton, pressed the department to follow up on Erickson and Clayton. Clayton reportedly confirmed Erickson’s involvement and explained that Erickson was ahead of Grossman, that he returned to the scene after parking his car at Grossman’s home, and that he was part of the lead position in that convoy. Butler believed this should have triggered immediate action.

Instead, once Sergeant Scott Shean took over as lead investigator, Erickson’s role was dismissed without the level of examination that would have been mandatory if the goal had been truth rather than conviction. The second driver was functionally written out early, before the evidence could prove too much.

From there, the case became controlled.

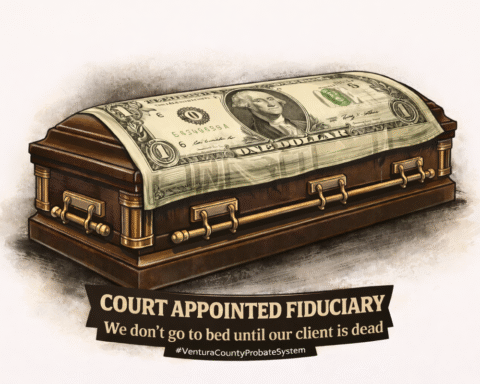

Erickson was ultimately charged with misdemeanor reckless driving, then allowed to resolve it through diversion, a quiet off-ramp that effectively erased accountability. Meanwhile, Grossman faced the full weight of second-degree murder prosecution. That contrast does not just feel disproportionate. It feels strategic.

Because reckless driving isn’t the point. The point is leverage.

If Erickson’s SUV was the first impact, or if his driving behavior materially contributed to the sequence that killed those children, then his legal exposure could have been enormous. And enormous exposure creates bargaining power. Bargaining power creates silence. Silence creates a clean narrative for prosecution.

It is impossible to look at the deal and not question whether it was designed to close the door on deeper inquiry. It is impossible to look at diversion and not wonder what prosecutors were protecting, what they were trading, and what they were afraid a full investigation would reveal.

This is where the personal history matters, not as gossip, but as context for credibility and behavior. Multiple sources have confirmed that Erickson comes from a family with a history of alcoholism, specifically involving his father and brother. That family dynamic is relevant because addiction patterns tend to echo through behavioral systems: secrecy, denial, minimization, and control. Those traits become particularly visible in crisis moments when accountability is on the line. Erickson’s conduct after the collision, from the alleged “you never saw me here” line to the immediate lawyer meeting, reads like the posture of someone reflexively managing exposure. The family history does not prove guilt. It speaks to the kind of psychological environment that can normalize concealment and the strategic avoidance of consequence.

Even without that context, the conduct stands on its own.

He didn’t stop. He returned without identifying himself. He allegedly urged silence. He allegedly lied about which vehicle he drove. He met with defense counsel immediately. His vehicle was never impounded. Evidence that didn’t match Grossman disappeared. Surveillance footage was mishandled and lost. The investigation narrowed instead of expanding. A diversion deal sealed the containment.

Then the media played its role. Rather than interrogating the second vehicle theory with the seriousness it demanded, much of the coverage mocked it as desperate, as if raising a legitimate alternate causation chain in a double-impact child fatality case is somehow offensive. Grossman’s claim that she never saw the boys because the lead SUV blocked her view in the dark was treated like a flimsy excuse instead of an evidentiary question that should have been tested through reconstruction, visibility analysis, and honest sequencing.

The system did not test the truth.

It defended a conclusion.

The Scott Erickson problem is that he never goes away. No matter how aggressively the narrative tries to bury him, the timeline keeps pulling him back up. The evidence log keeps pulling him back up. The missing evidence keeps pulling him back up. The surveillance mishandling keeps pulling him back up. The witness statements keep pulling him back up.

If the Grossman case is ever fully reopened in the court of public opinion or civil litigation, it won’t be because of theatrics or social media or outrage. It will be because the facts will no longer tolerate their own suppression.

A controlled prosecution depends on one thing: keeping the most dangerous alternative explanation off the table long enough for a verdict to harden into “truth.”

Scott Erickson is the alternative explanation.

And the case record reflects a justice system that treated that fact not as something to investigate, but as something to contain.

DISCLAIMER: Investigative reporting in high-profile litigation cases published by The Current Report is non-commercial, fact-based journalism; any project fees compensate research and reporting labor only, sources participate solely in accuracy verification, and final publication is approved exclusively by The Current Report after fact-checking is confirmed.