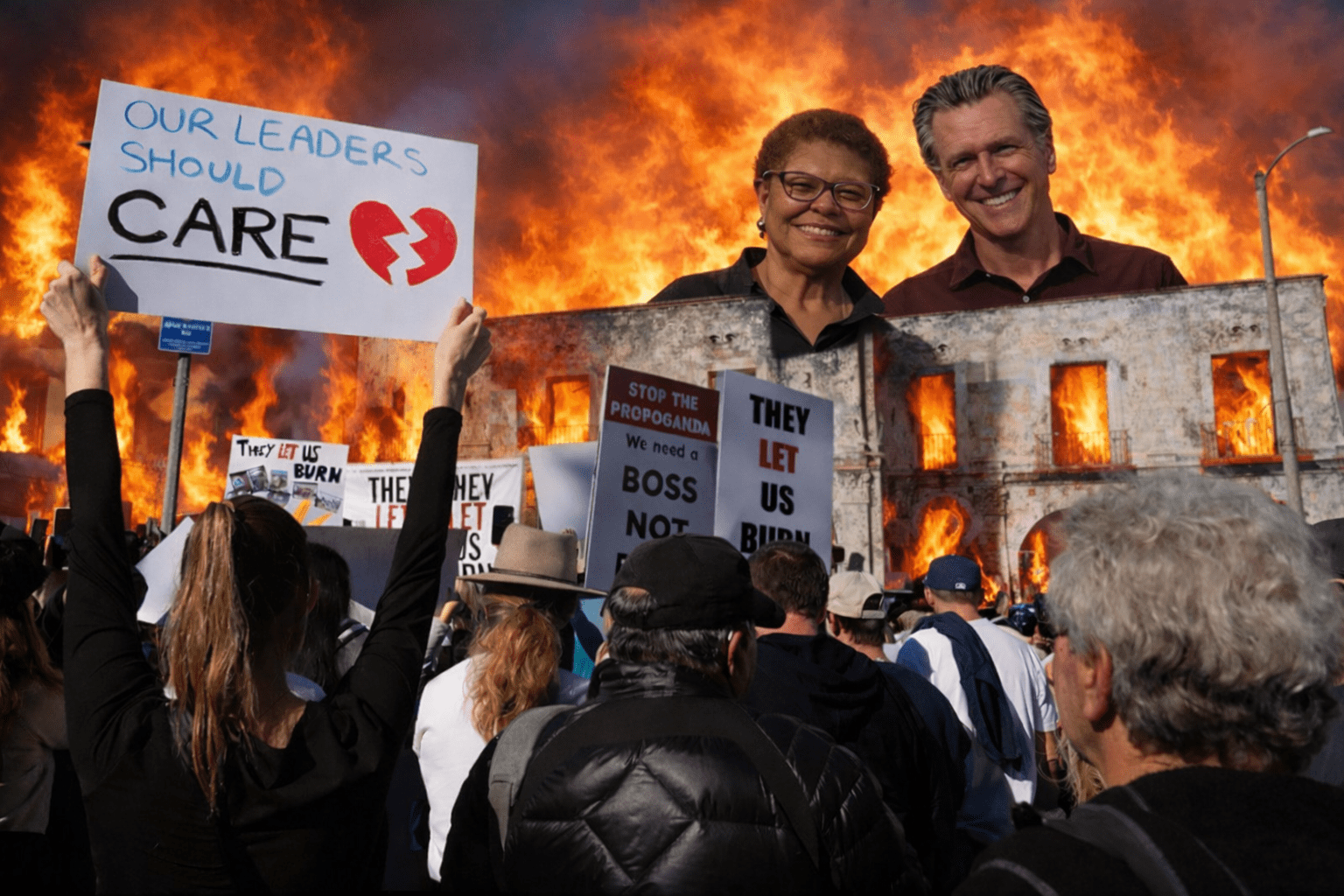

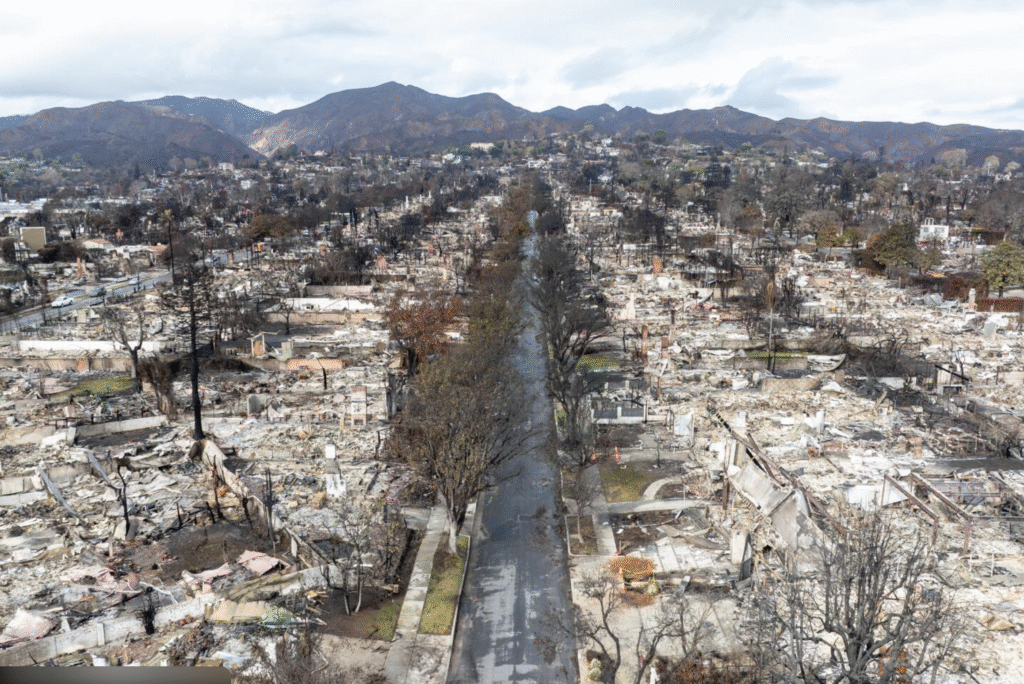

One year after January 7, 2025, the smoke has cleared, the ash has been hauled away, and the official narratives have been carefully sanitized. But the truth has not faded. That truth is what brought a community together at the “They Let Us Burn” rally, not for symbolism, not for performative grief, but to say out loud what leadership still refuses to acknowledge. This fire was preventable.

The rally was not about mourning alone. It was about memory and accountability. About rejecting the convenient fiction that this was an unavoidable act of nature rather than the foreseeable outcome of political neglect. The people who gathered understood something that many officials hope the public never connects. Disasters like this do not begin with flames. They begin years earlier, in budget votes, canceled meetings, ignored warnings, and leadership failures hiding behind bureaucracy.

Much of the public anger has focused, correctly, on Gavin Newsom and Karen Bass. Brush mitigation delayed. Emergency protocols treated as optional. Water infrastructure allowed to degrade in a state where wildfire is no longer an exception but a certainty. These are not abstract policy disagreements. These are decisions that carry consequences measured in lives and homes.

What far fewer people understand, and what the rally made impossible to ignore, is that responsibility does not end at the Governor’s office or City Hall. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors bears equal responsibility, and at the center of that failure is Lindsey Horvath.

The They Let Us Burn rally was not just a memorial. It was a line drawn. A refusal to let institutional failure be repackaged as inevitability. The people who gathered understood that accountability does not end with naming who failed. It begins with changing the structure that allowed failure to repeat itself.

That is where Tonia Arey becomes central to what happens next. Arey is running to replace Lindsey Horvath, the supervisor whose district burned while coordination collapsed and leadership went silent. Arey has committed to restoring emergency management authority back to the Sheriff, reestablishing regular coordination with Los Angeles County Fire, and treating preparedness as a governing obligation rather than a political inconvenience. And if the Board refuses to return that authority, she has pledged to use the full power of the Third District office to ensure emergency coordination does not disappear behind closed doors again.

That distinction matters. Because what January 7, 2025 exposed was not just a bad day or a bad decision. It exposed a governing philosophy that prioritized ideology over readiness and optics over lives. Fires do not begin when the first spark hits dry brush. They begin when oversight is dismantled, meetings stop, resources are stripped, and responsibility is diluted until no one is left to answer for the outcome.

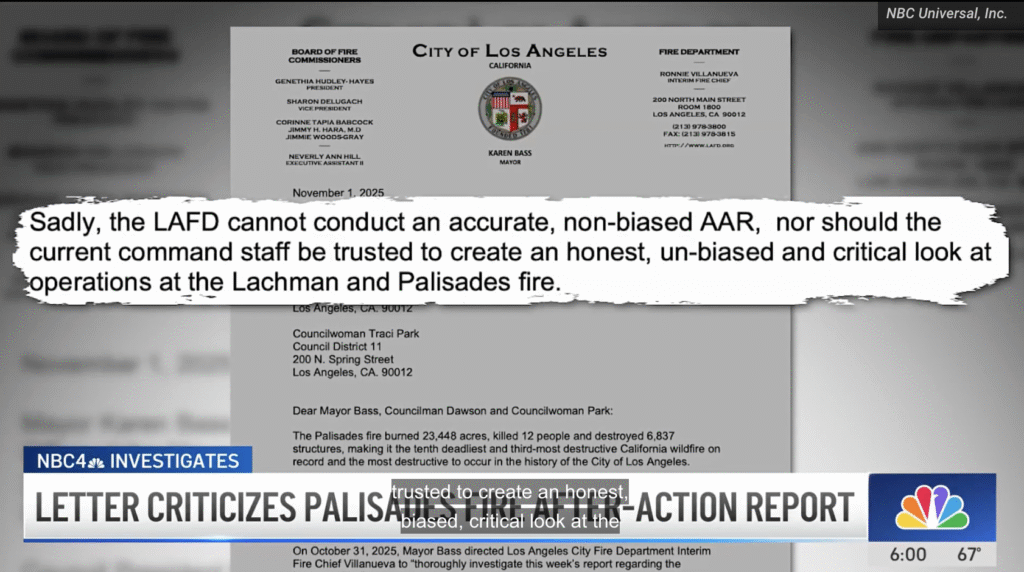

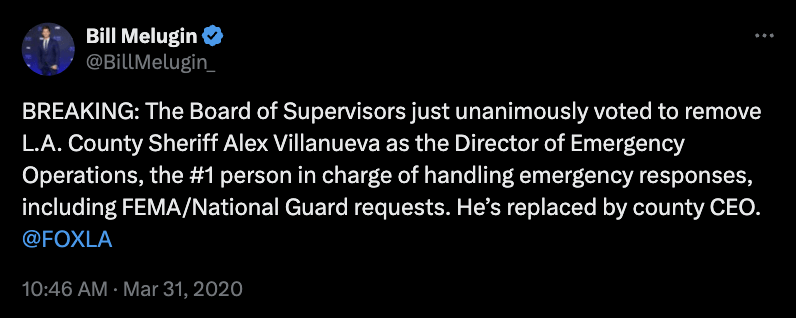

This was not the first wildfire that could have been prevented. The same failed leaders quietly whitewashed the after action reports following the 2018 Woolsey Fire, burying hard lessons instead of fixing the system. Nothing changed. If anything, the county performed worse this time, a staggering regression after years of warnings and promises. However, the incompetence of LA County leaders kicked into high gear in 2020 during the pandemic when the Board of Supervisors quietly stripped emergency management authority from then-Sheriff Alex Villanueva and reassigned it to themselves, routing control through the County CEO. That decision dismantled a structure that had existed for decades for a reason. When the Sheriff held emergency management authority under Villanueva, there were bi annual roundtable meetings involving the Board of Supervisors, the Sheriff, and Los Angeles County Fire. Emergency protocols were reviewed. Resources were assessed. Gaps were identified before crisis struck. It was not flashy governance, but it worked.

Once the Board took control, those meetings stopped.

The County CEO placed in charge of emergency management has since exited under an NDA, walking away with a reported two million dollar payout, leaving the public with silence instead of answers. But the damage was already done. Supervisors are not passive administrators. They function as mayors of their districts, wielding legislative power, budget authority, and quasi judicial influence. Horvath had the power and the obligation to continue those coordination efforts. She did not.

Instead, Horvath championed policies that weakened public safety. Defunding law enforcement. Starving fire services. Treating emergency preparedness as a political inconvenience rather than a non negotiable responsibility. Fire officials were already under resourced during what would be considered a routine fire season. When January 7, 2025 arrived, with predictable conditions and known ignition risks, the system failed exactly as experts had warned.

You cannot defund prevention, dismantle coordination, and then act surprised when the county burns.

The rally also marked a turning point in how this story escaped the boundaries of local outrage and became a national reckoning. That shift did not come from official press briefings or polished statements. It came from sustained public pressure, much of it driven by Spencer Pratt.

Pratt did not casually comment and move on. He immersed himself in the facts, timelines, and decisions that preceded the fire. Using social media the way investigative journalists once used front pages, he amplified firsthand accounts, challenged official narratives, and refused to let the fire be dismissed as an unavoidable natural disaster. His posts reached far beyond Los Angeles, forcing attention at levels local leaders never anticipated, including the President and the U.S. Department of Justice.

That attention mattered. It dragged failures in brush mitigation, emergency protocols, water management, and command authority into the national spotlight. What officials hoped would quietly fade instead became a matter of federal interest, precisely because someone with a platform refused to look away.

For Pratt, this was not performative outrage. It was catalytic. Watching leadership fail before the fire and then watching the same officials evade accountability afterward altered his trajectory. That motivation has now turned into action, with Spencer Pratt announcing his run for mayor, a development that underscores how profound the leadership vacuum has become.

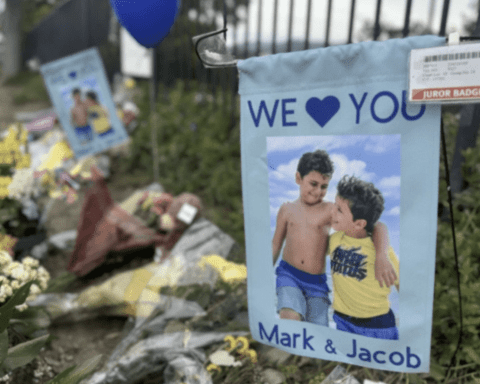

The They Let Us Burn rally was about truth in the aftermath of a catastrophe that affected a significant portion of LA County. It was about naming the systems and decisions that made catastrophe inevitable. It was about understanding that fires do not start on the day they ignite. They are built over time, through neglect, ideology, and the quiet erosion of responsibility.

The most damning reality is this. The system did not fail once. It failed repeatedly, predictably, and without consequence. And when citizens, activists, and outsiders are forced to do the work leadership abandoned, it is not a sign of healthy governance. It is an indictment. And now the community is making sure that history does not get rewritten again, and that no one forgets exactly who built the conditions that lit the match.