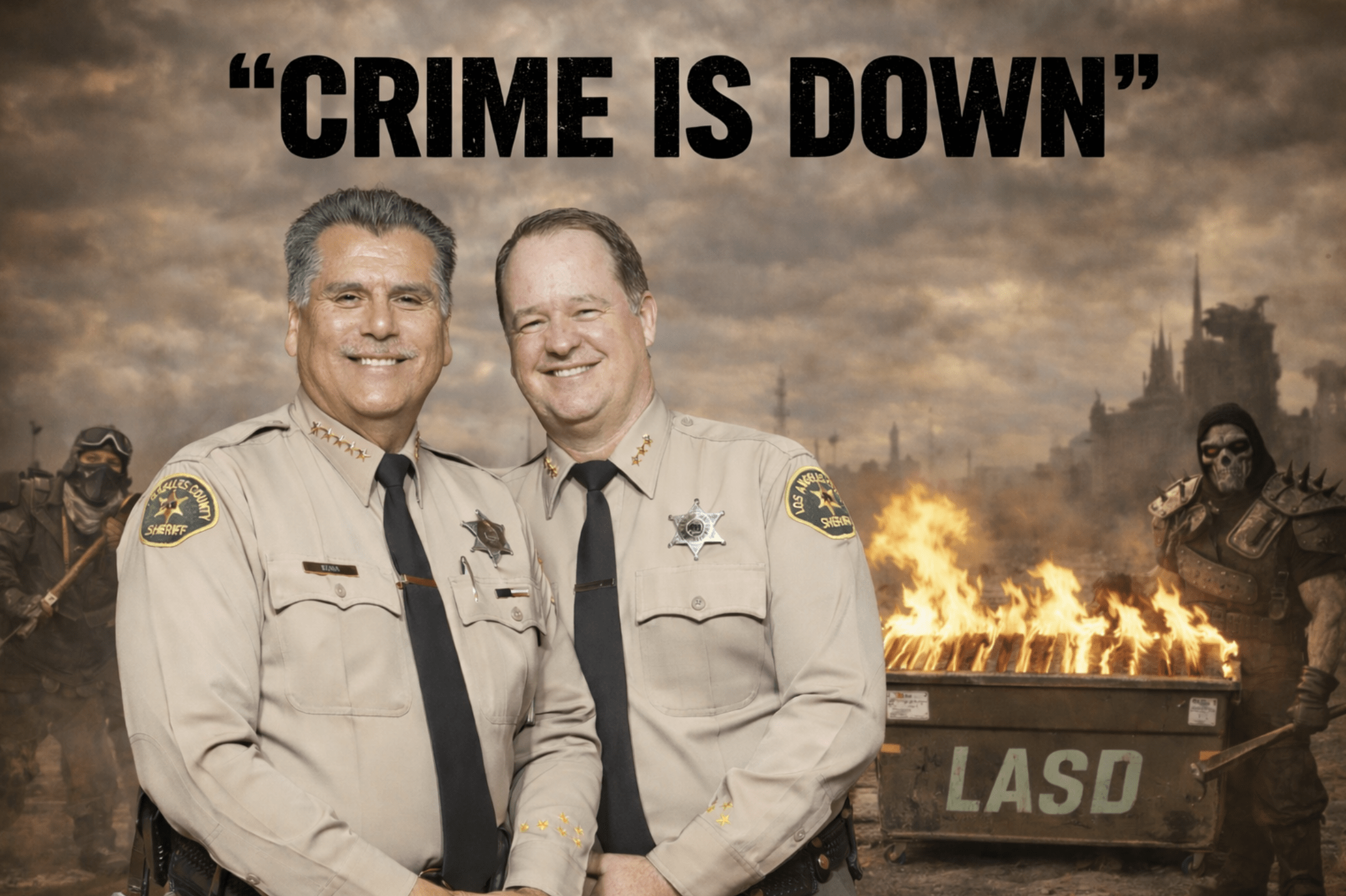

“Crime is down.”

That was the message Sheriff Robert Luna delivered to the Civilian Oversight Commission on January 22nd, 2025, wrapped in percentages, charts, and carefully framed statistics meant to reassure a public growing increasingly uneasy. According to Luna, Part 1 crimes have dropped by double digits, deputy-involved shootings are down more than forty percent, and new policies, training programs, and less-lethal tools are ushering in a safer era of policing in Los Angeles County.

But behind the talking points, a very different directive is being quietly delivered inside sheriff’s stations across the county, one phrase repeated often enough to become operational doctrine: “Slow your roll.”

That instruction has nothing to do with crime suddenly disappearing. It has everything to do with how crime is recorded, enforced, and ultimately presented to the public.

This week alone, as county officials touted declining crime rates, a new string of armed robberies ripped through The Commons at Calabasas and Westlake Village, areas long marketed as insulated from exactly this kind of violence. Shoppers were confronted at gunpoint in broad daylight, property was stolen, suspects fled, and no arrests were made. These were not isolated incidents. They were coordinated, bold, and carried out with the kind of confidence that comes when criminals know enforcement is thin and consequences are unlikely.

Yet residents were told “crime is down”.

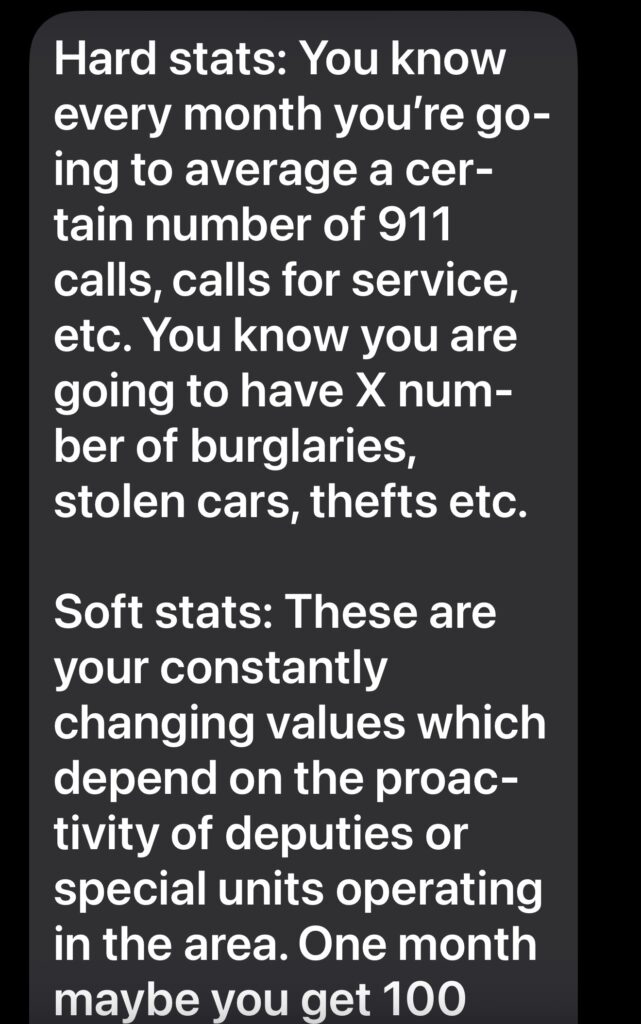

Inside the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, deputies tell a story that explains how both things can be true on paper, and completely false in reality.

According to multiple internal sources, deputies are being discouraged from proactive policing. Self-initiated stops are frowned upon. License plate reader hits are scrutinized. Looking for stolen vehicles, burglary crews, or suspicious activity is increasingly treated as a liability, not a duty. The safest course of action, deputies are told implicitly and sometimes explicitly, is to sit back, respond only when dispatched, and avoid generating activity that could later become an administrative problem.

This is what “Slow your roll” actually means.

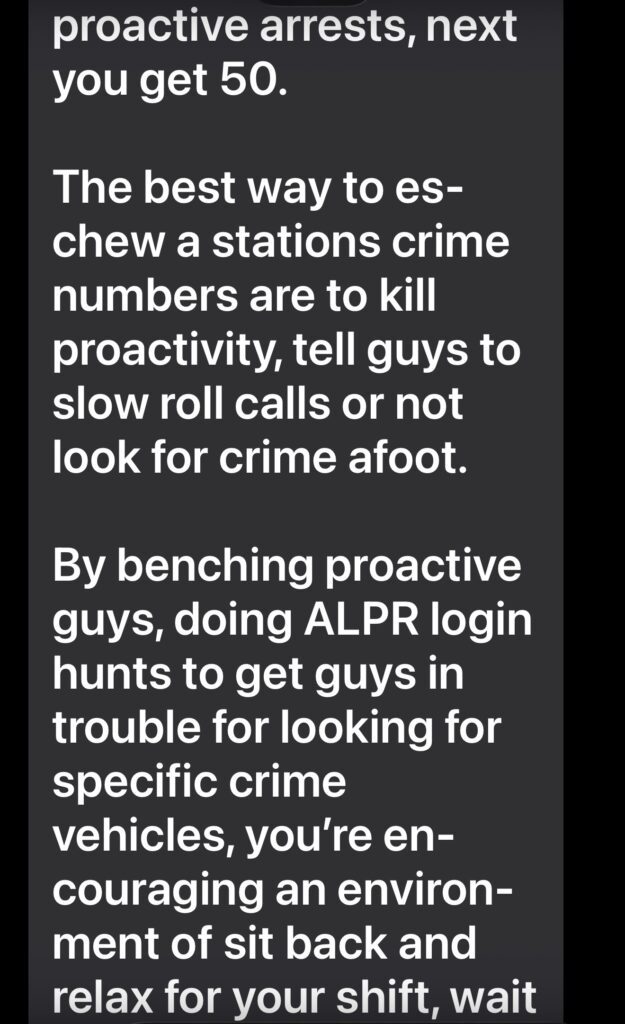

When deputies slow down, crime statistics do too, not because crime is decreasing, but because fewer crimes are being interrupted, fewer arrests are being made, and fewer incidents are formally documented. Hard realities like 911 calls, burglaries, auto thefts, and armed robberies do not magically vanish. What disappears is enforcement.

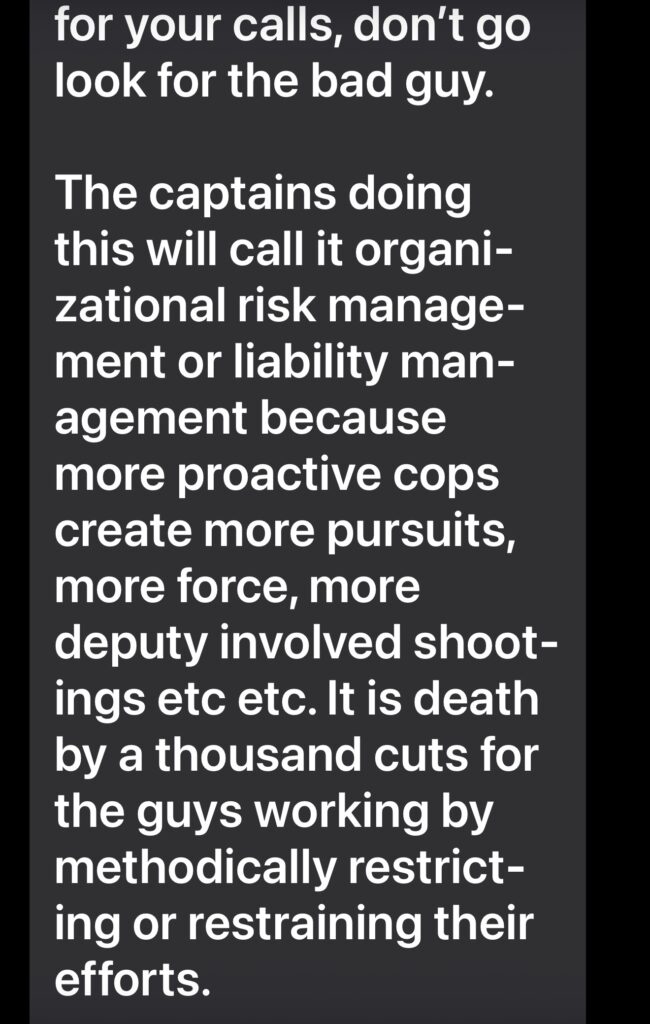

Sheriff Luna’s claim of a dramatic reduction in deputy-involved shootings follows the same pattern. The department credits new Tasers, crisis teams, de-escalation training, and revised use-of-force policies. But internally, deputies describe a simpler explanation: fewer proactive encounters produce fewer confrontations. If deputies are discouraged from engaging, there will naturally be fewer pursuits, fewer stops, fewer arrests, and fewer uses of force. That may look like reform from a podium, but on the street it looks like disengagement.

This is not a theoretical debate. In areas like Malibu, Calabasas, and Westlake Village, proactive policing has historically been the difference between opportunistic criminals passing through and organized crews setting up shop. When that proactivity is stripped away, crime does not retreat, it reorganizes. It becomes more confident. More visible. More dangerous.

Residents are noticing. They are changing their routines, warning each other online, and questioning why armed robberies are happening in places that once felt safe while officials insist everything is improving. The disconnect is not subtle. It is structural.

The illusion of falling crime is further compounded by who is no longer reporting it at all. Undocumented residents, increasingly fearful that any contact with law enforcement could trigger immigration consequences despite public assurances to the contrary, are choosing silence over risk, leaving entire categories of crime unreported.

At the same time, major retail chains, under direct orders from corporate headquarters, are quietly discouraging store-level crime reporting, prioritizing brand protection, insurance thresholds, and quarterly optics over accurate crime data. Theft, robberies, and repeat offenders are being logged internally, if at all, while police reports are avoided unless losses cross arbitrary financial lines. When victims are disincentivized, retailers are muzzled, and deputies are told to “slow their roll,” the resulting crime statistics do not reflect safer communities, they reflect a system designed to undercount crime by construction.

What the public is being sold is a narrative of reform and restraint. What deputies are living under is a culture of risk aversion, administrative fear, and leadership that prioritizes clean statistics over public safety. Arrests are down countywide, not because crime has dropped, but because deputies no longer trust command staff to support them when enforcement leads to scrutiny, discipline, or political fallout.

This is how a department can stand before an oversight commission and declare success while criminals walk away unchallenged from gunpoint robberies in upscale shopping centers.

Crime isn’t down. Enforcement is.

And when leadership tells deputies to “slow their roll,” the only thing that accelerates is the gap between what the public is told and what they are actually experiencing. Los Angeles County is being governed by optics, not outcomes — and the cost of that deception is being paid in fear, vulnerability, and eroding trust.

Because when safety becomes a numbers game, truth is the first casualty.