Wrongful convictions are rarely the result of one dramatic lie told in open court. They are more often built quietly, early, and methodically, before a jury is ever seated.

They begin in the investigative stage, where facts are supposed to be gathered, preserved, tested, and challenged. That is where truth is either protected or distorted. That is where justice either earns its credibility or loses it.

The Rebecca Grossman investigation is a case study in distortion. By the time the public encountered it, the narrative felt settled, as if the evidence naturally led to one unavoidable conclusion. But the appearance of certainty did not come from a flawless evidentiary record. It came from an investigation shaped to eliminate contradiction, to reduce complexity, and to lock the case into a single theory before alternative explanations could survive.

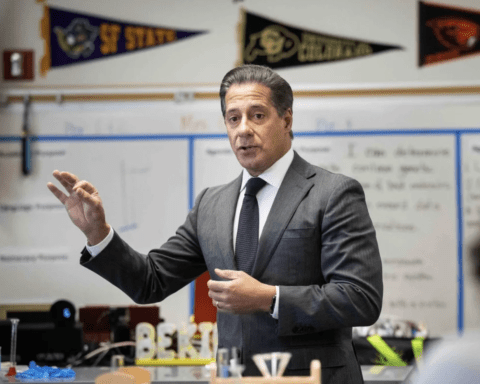

The name attached to the most consequential steering decisions is Detective Scott Shean.

This was not merely a failure to investigate. It was an investigation structured in a way that made full investigation impossible after the fact. When that happens, the court doesn’t evaluate the truth. It inherits a record that has already been edited.

The First 48 Hours: The Only Window That Matters

In fatal collision cases, there is a narrow window where evidence still exists in its original form. Surveillance footage has not been overwritten. Vehicles have not been repaired. Witnesses have not been influenced by the media. Digital systems still contain intact data. A true investigator treats those first 48 hours like an emergency because the truth is perishable.

That is why Shean’s involvement is so central. Because once he had authority over the investigation, the record shows something other than urgency toward truth. It shows an urgency toward closure. It shows a pattern where decisions consistently reduced the ability to later verify, test, and challenge the official storyline.

Investigations that seek truth preserve evidence in its strongest state. Investigations that seek certainty preserve it in its weakest.

The Surveillance Footage That Should Have Been Locked Down

There is one decision in this case that should stop the conversation immediately for anyone still trying to claim this was a rigorous investigation.

Instead of formally seizing and preserving the original surveillance footage, Shean recorded surveillance video on his personal iPhone, allowing the original source files to be erased. That is not a minor procedural slip. That is the functional destruction of objective evidence in a case where timing, sequence, lane positioning, and proximity are everything.

Original video files contain metadata. They contain native timestamps. They maintain frame integrity. They can be examined by independent experts without the distortions created by cell phone recording, compression, angle choice, screen flicker, and human discretion. Once you reduce original video to a phone recording, the evidence no longer stands on its own. It becomes something filtered, something interpreted, something easier to argue about and harder to scientifically validate.

And once the source files are erased, the strongest version of the truth is gone forever.

If an investigator wanted to preserve the cleanest possible record, he would lock down the originals immediately. If an investigator wanted to preserve a narrative, he could not choose a better method than degrading the most objective evidence in the case.

When “Recording” Evidence Becomes a Method of Controlling It

There is a difference between capturing evidence and capturing an impression of evidence. In serious cases, investigators do not take pictures of screens and call it preservation. They do not rely on personal devices and convenience shortcuts. They extract, seize, and book the original files because evidence is only as credible as its integrity.

By recording surveillance footage on a personal phone, Shean didn’t merely degrade quality. He controlled what became the surviving record. A cell phone recording makes choices for you. It picks angle. It distorts motion. It introduces blur. It limits what is visible at the edges. It makes time stamps harder to verify. It creates a weaker foundation that prosecutors can still use, but which defense experts can no longer fully reconstruct.

That is not an accident. That is an outcome created by choice.

In an investigation driven by truth, you preserve the strongest version of evidence. In an investigation driven by certainty, you preserve the weakest version that still supports your theory.

Witnesses Reported Multiple Impacts, Yet the Investigation Stayed Single-Minded

Multiple witnesses reported hearing separate impacts, distinct in time and sound. That is not a throwaway detail. That is not “noise.” That is evidence of sequence. It suggests a collision event that may not align with a simple one-impact, one-driver story.

And here is where this investigation becomes indefensible: these weren’t vague impressions. These were consistent accounts, overlapping in key details, describing the same core sequence.

Susan Manners could not describe the color of the vehicle involved, but she was clear about the most important part, she heard two distinct impacts. That matters because it supports the existence of two separate collision events, not one continuous blur.

Yasamin Eftekhari testified to a second impact and stated that the black vehicle was directly in front of the white vehicle. Jake Sands described the black vehicle in front of the white vehicle in the far-right lane. The boys’ mother said the last thing she saw coming at her was a black vehicle.

Even more damning, the video evidence does not contradict them. It reinforces them. The footage shows the black car directly in front of the white vehicle, not offset, not behind, not merely “in the area.” Directly in front.

A competent investigator would treat this as urgent. It would trigger immediate follow-up. Witnesses would be revisited carefully and methodically. Timelines would be reconstructed. Their accounts would be mapped against physical evidence, damage patterns, debris distribution, and body positions. If multiple impacts occurred, the investigation would have to ask why and how.

But Shean did not meaningfully pursue those witnesses who described separate impacts. He did not reconcile their testimony with the narrative he was already advancing. He did not treat their accounts as potentially clarifying evidence. He treated them as inconvenient variables.

That is the behavior pattern of tunnel vision. It is what happens when an investigator stops investigating and starts managing contradiction.

The Alternative Driver Question: Raised, Then Neutralized Through Inaction

The most glaring red flag in this entire case is not what Shean did. It is what he refused to do.

A credible investigation does not ignore alternative actors who are directly positioned in the sequence of events. In this case, there was a documented alternative driver directly in front of Grossman’s vehicle. A witness suggested investigators speak directly to him. That should have been pursued aggressively because that is what real investigations do. They test possibilities. They do not assume away inconvenient facts.

But there is more.

According to information that has circulated among those closely tracking the investigative record, Royce Clayton called in the very night of the collision identifying Scott Erickson as involved. A name was reportedly placed on the table while the scene was still fresh, while evidence still existed in its raw form, while vehicles were still where they were, before repairs, before storylines, before convenient forgetting.

And yet, when Shean took over the investigation the next day, the record reflects something so reckless it borders on intentional: he did not treat Erickson as a meaningful investigative target requiring urgent elimination through forensic science. He did not conduct the kind of direct follow-up that serious cases demand. He did not confront him as a person of interest. He did not inspect the vehicle. He did not preserve the opportunity to test the most dangerous question in the case.

Later attempts to frame Erickson merely as a “witness” are not credibility repairs. They are narrative protection.

Failing to examine an alternative actor accomplishes one key thing: it prevents the record from ever proving the alternative mattered.

A refusal to look is not the absence of evidence. It is the creation of ignorance. And ignorance becomes the prosecution’s shield.

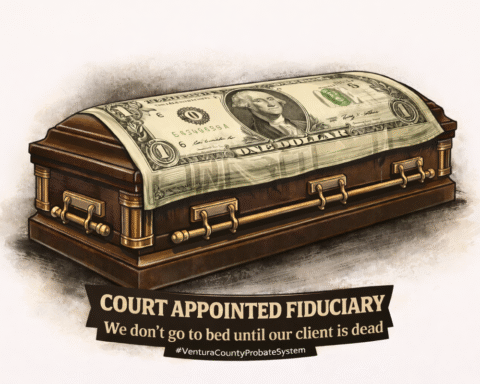

Evidence That Disappeared

Then came the physical evidence logged at the scene that later went missing, reportedly inconsistent with Grossman’s vehicle. Evidence does not just vanish without consequence. When it disappears, the case becomes compromised, the chain of custody becomes suspect, and the integrity of the entire record is threatened.

In an honest investigation, missing evidence triggers a crisis response. Investigators stop. They reassess. They reopen. They audit custody. They acknowledge that the record is now incomplete and potentially tainted.

Shean did none of that.

The question is not only who physically removed the evidence. The deeper question is who controlled the investigation at the time the evidence was vulnerable. Who had access. Who had authority. Who had the power to decide whether missing evidence would be treated as catastrophic or treated as irrelevant.

Because the effect of missing evidence is always the same. It removes contradictions. It simplifies the narrative. It strengthens the chosen theory by eliminating what doesn’t fit.

When evidence disappears and the investigator does not flinch, it is no longer an investigation. It is narrative preservation.

Sources Point to a Larger Containment Effort

And according to sources familiar with the broader ecosystem surrounding this case, the failure to treat Scott Erickson as a serious investigative target may not have existed in a vacuum.

Those sources allege that former Major League Baseball player Rick Thurman, along with a well-known baseball agent Dennis Gilbert, have intimate knowledge of statements indicating Erickson privately acknowledged some level of responsibility connected to the crash. These same sources further allege that Thurman may have played a role in coordinating post-collision actions aimed at managing exposure, including assisting in the removal or disappearance of potentially critical evidence tied to the black vehicle.

None of these claims have been adjudicated in court. They are allegations. But their existence matters for one reason: they align with what the investigative record already shows, which is that the alternative-driver question was not only raised, it was neutralized through inaction, and the evidence trail was allowed to degrade, vanish, or die before it could ever threaten the official storyline.

If the justice system were healthy, the presence of such allegations would trigger immediate independent review. Instead, they exist in the same place where so many inconvenient truths end up, outside the courtroom, because the investigation never built a record capable of absorbing them.

Tunnel Vision Isn’t a Psychological Mistake. It’s Professional Misconduct.

Tunnel vision gets described as a natural human weakness. That framing is convenient because it removes accountability. It allows investigators to present steering behavior as mere cognitive error. But tunnel vision in law enforcement is conduct. It is the repeated professional choice to ignore alternatives, to minimize contradiction, and to maintain certainty even when the record demands doubt.

Shean’s conduct fits that pattern precisely.

He reduced original surveillance to a degraded phone recording and allowed source files to be erased. He failed to pursue witnesses describing multiple impacts and consistent vehicle positioning. He ignored direct suggestions to seriously investigate an alternative driver placed directly in the sequence. He did not forensically exclude that driver. He continued forward despite missing physical evidence that undermined the official narrative.

Those are not oversights. Those are decisions.

And those decisions built the case that prosecutors later presented as inevitable.

The Conviction Was Set in Motion Before the Trial Ever Began

Trials do not decide the truth if investigations do not preserve it.

Once Shean made the key choices that limited evidence integrity, ignored alternative explanations, and allowed contradiction to be erased, the outcome was no longer a fair contest of competing theories. Prosecutors inherited a record already shaped for narrative clarity. Jurors inherited a record stripped of its most dangerous ambiguities. The public inherited a storyline that felt certain because the investigative process had already removed the messy parts.

That is the mechanism of wrongful conviction. It isn’t always lies. Sometimes it’s far subtler. It’s a case built on omission and the destruction of doubt before doubt can be examined.

Call It What It Is: Investigative Steering

The most dangerous force in this case was not public outrage. It was investigative certainty.

Scott Shean did not merely stop investigating. He structured the investigation so that alternative explanations could not survive and the record could not contradict him. That is how unsafe convictions are built. Not always through corruption that can be easily proven, but through decisions that turn the justice system into a narrative machine.

If the system wants to stop wrongful convictions, it has to stop treating tunnel vision as a harmless human flaw. It has to treat it as what it is in practice: a professional failure that can kill the truth long before the courtroom ever has a chance to hear it.

And until that standard is enforced, this case will not be the last.