The child abuse crisis in Los Angeles and the high price of persistent failures.

By Thea Eskey

There is no greater injustice than the abuse of a child. Children are defenseless, depend on adults for their safety, and their life outcomes are inextricably linked to the care they receive. The deleterious consequences of abuse include a myriad of behavioral, health, and economic impacts. These effects endure a lifetime, more often than not are cyclically repeated and require strong interventions to overcome. Unfortunately for the children of Los Angeles, life-saving interventions from the Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) are severely lacking. As the key child welfare agency in the county, DCFS is responsible to provide a strong back stop to protect the most vulnerable in society. This duty includes removing children from harmful home environments responsible for trauma. Instead of fulfilling its obligation, DCFS knowingly allows children to remain in abusive homes due to a misguided policy that places family reunification above health and safety. As a result, it is no surprise that multiple abused children have remained in their homes, where they have died as a direct result of DCFS failures. What is truly shocking however is the lack of real and meaningful change in the Los Angeles child welfare system after so many innocent children died from horrific abuse and systemic neglect.

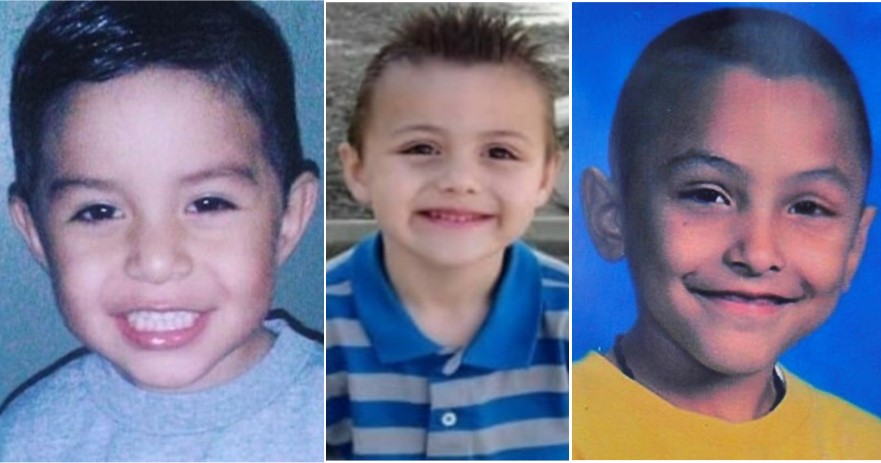

In May 2013, Gabriel Fernandez was rushed to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, covered in injuries from head to toe. He was pronounced dead two days after arriving at the hospital. According to documents produced in the trials of his mother, Pearl Fernandez, and her live-in boyfriend, Isauro Aguirre, they subjected the 8-year-old boy to unspeakable torture. Gabriel was shot with a BB gun, beaten all over his body, and forced to eat cat litter and his own vomit. Instead of being given a bed to sleep in, Gabriel was blindfolded, handcuffed and locked in a small cabinet in his mother’s room. Throughout the course of his tragically short life, many people, some of whom were mandated reporters, witnessed signs of his abuse and alerted DCFS. Near the end of Gabriel’s life, a risk assessment conducted by DCFS showed he was at high risk for abuse. Yet, no action was taken and Gabriel remained in the home with his abusers.

In June 2018, 10-year-old Anthony Avalos was tortured and murdered by his mother, Heather Barron, and her live-in boyfriend, Kareem Levia. In the last days of his life, Anthony was whipped violently all over his body, was held upside down and dropped on his head, had hot sauce sprayed in his eyes, mouth and nose and was made to kneels on kernels of rice for hours on end without rest. In many ways, the abuse Anthony suffered mirrors Gabriel’s. Both children were brutalized by a parent and their partner. Both children were systematically ignored by DCFS. According to a lawsuit filed on his family’s behalf by attorney Bryan Claypool, Anthony’s case was credibly referred 13 times to the Antelope Valley DCFS offices with “…countless red flags.” Despite these repeated warnings, no intervention was made on behalf of Anthony or his six half-siblings to remove them from the home where the abuse occurred.

A year after Anthony’s death, 4-year-old Noah Cuatro died. According to Noah’s autopsy, the cause of death was determined to be asphyxiation and blunt force trauma. He also showed signs of repeated sexual assault trauma, such as sodomization. His death occurred after multiple reports of physical and sexual abuse were made to the Antelope Valley DCFS offices. In fact, Susan Johnson, a social worker assigned to Noah even went so far as to obtain a court order that demanded the child’s removal from the home. After receiving that order, DCFS did not seek Noah’s immediate removal, leaving him in the dangerous home environment for weeks, until he died. According to grand jury testimony given by Johnson, the court order was overruled by her direct supervisors and they dismissed her from continued work on Noah’s case.

In order to better understand the reason that these incidents of negligence continue to accumulate, I spoke with Dr. Linda Degutis, a public health professor at Yale University, who previously worked at the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC’s) Violence Prevention Unit. I asked Dr. Degutis why bureaucratic systems such as DCFS seem to be so well adjusted to fail and so reluctant to make change. Her simple answer was jaw-dropping. “Because,” she explained, “in their minds the failures cost less than the solutions.” But, are the material costs associated with child abuse in fact less expensive than any potential solution? The answer is no according to a 2012 press release about the costs of child abuse issued by the CDC. The CDC noted that the United States spent a massive $124 billion to respond to child maltreatment in 2012. Adjusting for inflation, in 2021, that amount would be approximately $144 billion. In the state of California alone, $12.5 billion is spent on child abuse annually. If even a fraction of these amounts were spent on proactive solutions to deter child abuse, imagine the benefits to individuals and communities.

Due to the exorbitant sums spent every year to respond to child abuse, I was interested to know whether Dr. Degutis considered child abuse to be a public health crisis. “Yes, I do,” she answered. I followed up by asking why she thinks there has not been a comparable public health response from government that approaches the level of attention focused on other public health issues, such as cancer, AIDS and COVID. “People just don’t understand it,” she replied, “For the most part, people think, ‘I don’t know anyone who’s been abused,’ so it’s not a priority in their minds the way cancer is. Even with AIDS, it was slow going to get the public’s attention. It took almost 10 years to develop an effective treatment.” This lack of public recognition of the child abuse crisis is marked each year by the awful toll of abused, traumatized and dead children.

On April 10, 2021, news broke of three children under the age of five who were found drowned in an apartment in Reseda. Their mother, Liliana Carrillo, was missing. Eventually, she was found, arrested and named as the prime suspect in the children’s alleged murder. On April 19, 2021, Carrillo was arraigned for three counts of murder after confessing to her role in their deaths. According to court documents filed in both Los Angeles and Porterville, Ms. Carrillo was in the middle of divorce proceedings with the children’s father, Erik Denton. The Porterville court issued, at the request of Denton, an order for a mental health evaluation of Carrillo and an emergency order granting him primary custody of the children. In interviews on Fox 11 and in the Los Angeles Times, Denton’s cousin, Teri Miller, an emergency room physician, confirmed that Carrillo was suffering a mental health crisis and that Denton sought the orders to protect his children and Carrillo from harm.

After these orders were issued, Carrillo fled with her children to Los Angeles, settling in Reseda. It was there that Carrillo obtained a temporary restraining order against Denton, alleging that he was sexually abusive to the eldest child. The order was issued towards the end of March and was set to expire at the couples next court hearing on April 6, 2021. From the end of March until the death of the children, both Erik Denton and Teri Miller frantically sought the intervention of DCFS and the LAPD to no avail. In fact, DCFS went to visit Carrillo in the throes of a mental health emergency and determined that she was of no danger to the children, allowing them to remain in her custody.

This tragic incident exposes another facet of abuse, its indirect costs, which are less visible but just as important as the direct costs. In the case of Liliana Carrillo, her untreated mental illness that led to the death of her children will be absorbed as an indirect cost by DCFS and the criminal justice system. While the direct costs deal with the simple mathematics of how much is being spent to treat the health outcomes of affected children, indirect costs are expressed through things like substance abuse, productivity losses, PTSD and other mental health problems. In the CDC-Kaiser Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) study conducted in the late 90’s, the major finding was that early childhood adversity has lasting impacts, many of which have indirect costs for the victims. The study also highlights that these indirect costs are expressed across various systems, such as public health, education, criminal justice and welfare. In the case of DCFS, the continued failure to protect children from harm imposes high indirect costs on the county’s criminal justice and public health systems.

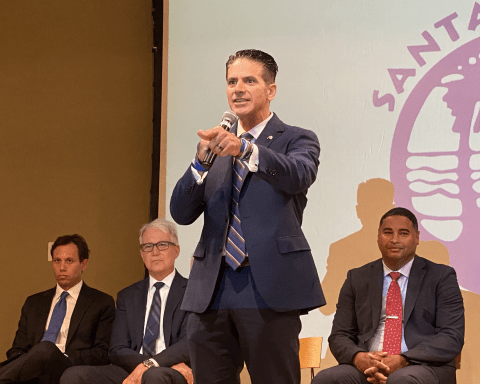

No one is more familiar with the indirect costs associated with child abuse than Deputy District Attorney Jonathan Hatami in the Complex Child Abuse Unit of the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office. A prosecutor for fifteen years, he sees the indirect costs of abuse in his work every day. When I asked him about these indirect costs, he said, “…many children who are abused, like you said, we end up having to have an extra cost. It’s the cost of therapy down the line, it’s the cost of getting involved in addictive conduct behavior and drugs, it’s low self-esteem, not being productive in society, not being able to hold a job, not being able to keep a job, not even being able to get a job. Also being abusive yourself. Many people who are abused end up abusing again and again and these things add to the actual cost of not handling child abuse appropriately to begin with.”

Aside from seeing it in his work, Hatami, himself a survivor of child abuse, has experienced his own set of indirect costs. He explained to me when I spoke with him that the abuse that he suffered as child left him with anger issues. “I thank the military for helping me get focused,” Hatami said. He also noted that it is imperative to underscore that child abuse does not happen in a vacuum. Even though the Antelope Valley is 80 miles away from his office in Downtown, “communities are interconnected and interrelated,” Hatami said, “I just did a presentation for Pico Rivera and I don’t live in Pico Rivera. You know, I specifically told them that we’re all Angelenos and so child abuse and issues with children is very interrelated because what happens to children in Antelope Valley can affect Malibu, Long Beach, Torrance, all these different areas. La Mirada, Pico Rivera and so it’s very interrelated and everyone’s mobile so people move around LA County all the time so if we can’t take care of children in certain areas it will end up affecting children in other areas as well.” In summary, he said, “people need to realize that just because something really major happened in Antelope Valley, doesn’t mean that it can’t affect Los Angeles in other areas because it can.”

Following Gabriel’s death, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors organized a blue-ribbon commission in 2014 to examine the failures in his case. The report’s main conclusion stated, “[t]he Commission unanimously concluded that a State of Emergency exists, which requires a fundamental transformation of the current child protection system.” Unfortunately for the most vulnerable Angelenos, it appears that the transformation has yet to be realized. These municipal defects continue to this day, while children need fearless and tireless advocacy to ensure their rights and safety.

Owing to his years of experience, I asked Hatami what he thinks the inciting action will be that will finally spark the desperately needed changes in the child welfare system in Los Angeles County. “You know, I thought Gabriel would be that moment,” he said, “So, you know, I’m at a loss to know when that moment’s going to be. I really thought Gabriel would have been that moment and it wasn’t so I don’t know.” He paused for a second and then offered, “I’m going to keep beating that drum and I’m going to keep fighting for children but I think that’s a tough question. I’m not sure. I’m not sure what it is but…I don’t know, cause it seems like they start getting all hyped up when children are killed and the after a few years they don’t care about it anymore and it happens again, and again and again.” After another pause, “I don’t know, I don’t know,” he exclaimed, “It’s sad to say maybe…I mean, I don’t know, I don’t know. Maybe they need, maybe…” He trailed off once again. After collecting his thoughts, Hatami offered this powerful final summation, “I don’t know, it’s a good question. I’m at a loss for that because I think, more and more children getting killed, why does that have to be the reason to make change? Shouldn’t we just make change because it’s the right thing to do? Why do we need children to die to do that? But it seems like they don’t want to do anything unless a child dies so I don’t know what it’s going to take to make changes exactly happen. I wish I knew cause if I did, you know, I would start talking about it but I don’t know.”

Follow Us