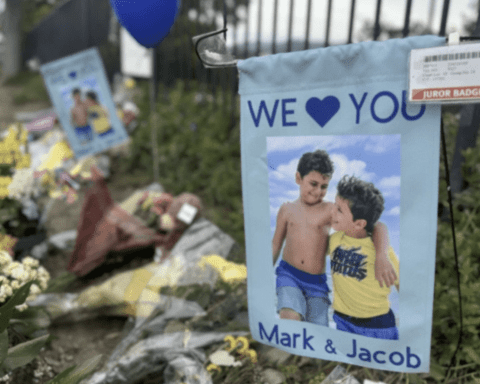

The Rebecca Grossman prosecution has been marketed as a clean morality play. A wealthy defendant. Two dead children. A “slam dunk,” according to the prosecution. A conviction wrapped in grief, sealed in headlines, and defended as if any question were sacrilege.

In a politically charged climate, the public was handed a storyline that required no thought, only outrage. It was engineered for maximum emotional certainty, the kind that makes people feel righteous simply for having an opinion. But criminal convictions are not supposed to be belief systems. They are not cultural verdicts. They are not prewritten scripts where the courtroom serves as a stage and the jury is expected to rubber-stamp the ending. They are supposed to be the product of due process and admissible proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

The Grossman case was the opposite.

That standard was not merely strained, it was strategically managed. And that is not rhetoric. That is the only honest way to describe what happens when a criminal prosecution becomes structurally dependent on what a jury is not permitted to hear. Because the closer one gets to the evidentiary record, what existed, what was ignored, what was never investigated, what was excluded, and what was never disclosed consistent with constitutional obligations, the more obvious the truth becomes.

The Grossman conviction was obtained in a case saturated with unresolved factual issues, a compromised investigative pathway, and evidentiary suppression that goes to the core of guilt and causation. That is not a defense talking point. It is what the record is increasingly confirming.

That record did not begin to surface accidentally. It emerged only after the Iskander family rejected a substantial settlement offer, an enormous financial sum, from the insurance carrier and chose instead to proceed with full civil litigation. That decision matters. Settlements end scrutiny. Litigation creates records. By refusing to close the case quietly, the Iskanders triggered sworn depositions, compulsory discovery, and evidentiary disclosures that the criminal prosecution never had to confront in open court. What followed was not conjecture, but testimony under oath that materially expanded reasonable doubt and redirected attention toward what the criminal case worked to avoid, the unresolved role of Scott Erickson and the possibility of a multi-vehicle causal sequence.

Due to the Iskanders’ decision to move beyond an anticipated out-of-court resolution, sworn depositions are now prying open doors the criminal prosecution worked overtime to keep closed. Civil discovery does what political prosecutions fear. It creates a record that cannot be edited into something more palatable. It locks witnesses into testimony where selective memory becomes a perjury risk. It forces admissions where silence once protected careers. It turns “we didn’t pursue that” into an evidentiary confession. And it is now revealing, in real time, the investigative failures and omitted lines of inquiry that were never meaningfully presented to the jury, despite their direct relationship to causation, culpability, and reasonable doubt.

The core legal issue is that causation was never clean, so the jury was forced to pretend it was. Under California criminal law, Grossman’s conviction required proof not simply of involvement, but of legal causation, that her conduct was a substantial factor in the deaths and that no alternate causal sequence or intervening factor materially undermined that theory. That standard matters because criminal law is not merely about identifying a person who was present during a tragedy. It is about proving, to the strictest evidentiary level our justice system claims to demand, exactly what occurred, what the sequence was, how the impacts happened, what caused the deaths, and whether any competing causal explanation creates doubt that cannot be overcome by assumption, emotion, or narrative.

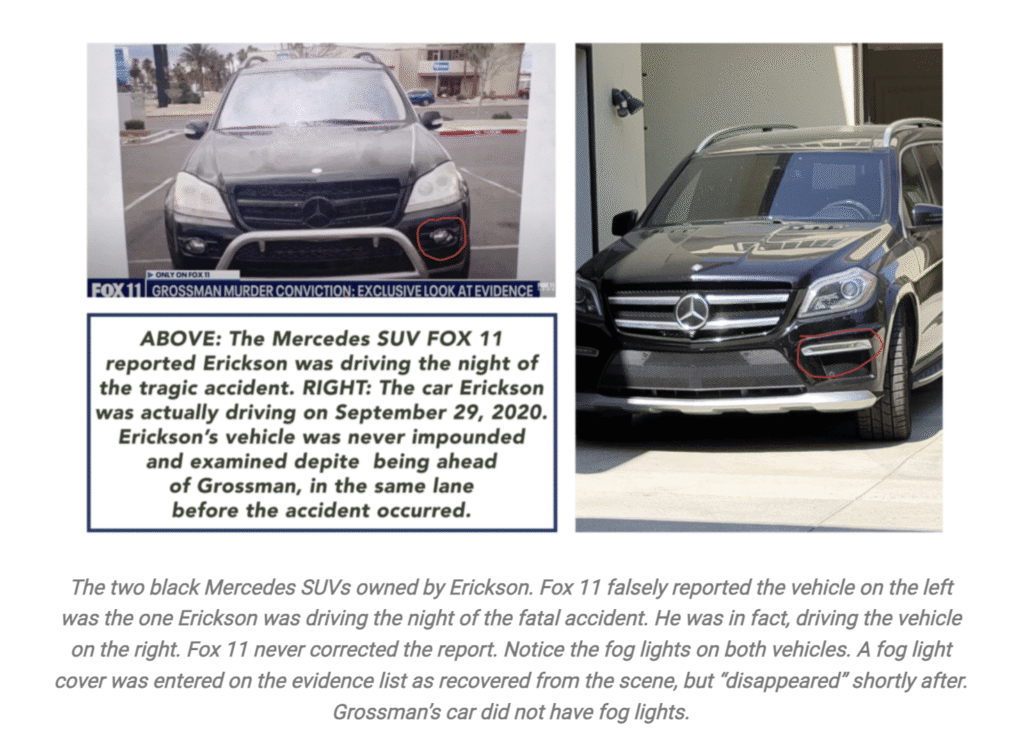

But from the outset, this case contained a destabilizing variable the prosecution treated not as evidence to be tested, but as a threat to the desired narrative: the presence and potential involvement of a second vehicle. That second vehicle has a name attached to it, Scott Erickson, who was driving at a high rate of speed three seconds ahead of Grossman in the same lane, making it highly probable he struck the children first. This is not a sidebar. This is not internet speculation. This is a material evidentiary issue with constitutional weight. Civil testimony now emerging exists only because the case moved beyond settlement, and that testimony is placing Erickson’s vehicle, speed, position, and lack of forensic scrutiny squarely back into the causation analysis the jury was never allowed to fully confront.

The introduction of a second vehicle into the crash sequence is not merely a different interpretation. It goes directly to who struck whom, when, and with what force. It goes to whether Grossman’s vehicle caused both impacts or whether another vehicle did. It goes to whether the prosecution’s causal theory was incomplete or incorrect. And most importantly, it goes to whether the jury was deprived of evidence necessary to evaluate that question with the seriousness it required.

The jury was not allowed to fully confront that issue. And that was not incidental. It was structural. When prosecutors build a case around a singular, simplified causal chain, they do not merely focus the issues. They eliminate competing ones. When they succeed, jurors do not necessarily convict because the evidence was airtight. They convict because the courtroom never gave them the full picture that could have made them hesitate. And hesitation, under the law, is reasonable doubt.

Civil depositions are now documenting an investigation that failed basic standards. In the civil depositions in Iskander v. Grossman et al., testimony is surfacing that should alarm anyone who cares about lawful prosecution standards. Not because it is dramatic, but because it is fundamental.

Deputy Rafael Mejia’s testimony is central to that concern. Mejia acknowledged under oath that he made the decision early on that Grossman was solely responsible and, based on that conclusion, did not investigate Scott Erickson as a potential suspect in the children’s deaths. That decision was not the result of comprehensive forensic testing. It was made despite evidence Mejia himself documented that did not fit a single-vehicle narrative. That evidence included debris inconsistent with Grossman’s SUV, indications of multiple impact points, and witness statements describing two distinct impacts, approximately 3-5 seconds apart.

Rather than prompting expansion of the investigation, that contradictory evidence was effectively sidelined. And critically, much of it did not simply remain untested. It went missing.

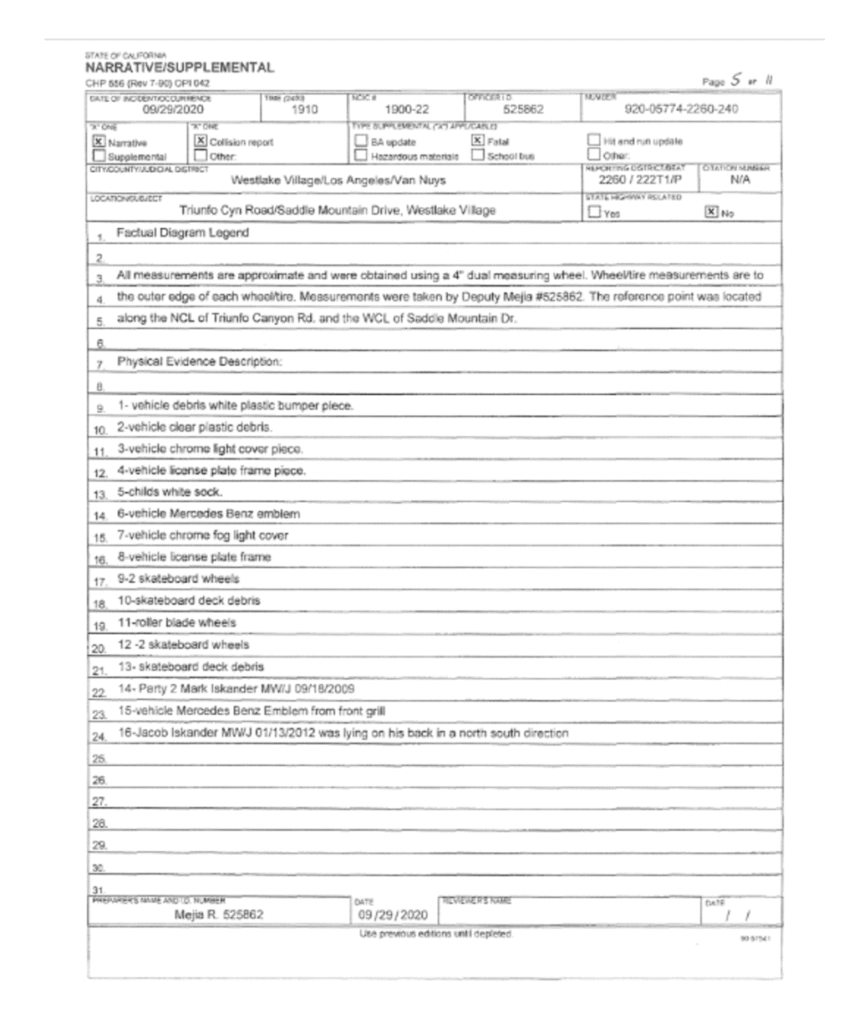

Physical items logged at the scene that did not match Grossman’s vehicle, including a chrome fog light cover and a license plate frame, were documented and then disappeared from the evidence chain without explanation. Original surveillance footage that could have clarified vehicle positioning and sequencing was never preserved in its native digital form. Instead of securing and archiving the original files, deputies recorded a monitor with cell phones, allowing crucial visual evidence showing multiple vehicles in motion to vanish without forensic authentication. These were not clerical oversights. They were failures that occurred after a conclusion had already been reached.

Mejia’s deposition makes clear that the investigative narrowing happened first, and the evidentiary losses followed. That sequence matters. In any legitimate vehicular homicide investigation, evidence that contradicts an early theory should trigger deeper inquiry, not abandonment. When evidence logged by an investigating deputy later disappears, and that evidence undermines the conclusion the deputy has already reached, the integrity of the entire investigative process comes into question.

This is not investigative discretion. It is investigative foreclosure.

The admissions now being locked into sworn testimony describe an investigatory process that deviated from the standards required for a fatal collision involving multiple potential vehicles and multiple victims. The civil case is exposing decisions that, in any serious vehicular homicide investigation, would be indefensible. Causation was assumed, not proven. Alternatives were dismissed, not tested. And once the case was framed as closed, evidence inconsistent with that framing ceased to exist in any meaningful evidentiary form.

Suppression and exclusion in this case were not strategy, they were case engineering. There is a difference between trial strategy and case engineering. Trial strategy is how facts are argued. Case engineering is how facts are controlled. Strategy is persuasion. Engineering is containment. This case bears the hallmarks of the latter, not just in what was argued, but in what was never allowed to be fully litigated.

The Current Report has documented that recordings and internal investigative discussions existed that raised questions about whether one vehicle could account for the debris field and sequence of impacts, including discussions suggesting another car may have struck one of the children. That kind of material is not extra. It is not fringe. It is not optional. It is the type of evidence that can crack a prosecution theory at its foundation. If those materials existed and were not meaningfully explored, disclosed, or admitted, the legal implications are severe.

Under Brady v. Maryland and its progeny, the prosecution has an affirmative constitutional obligation to disclose exculpatory and impeaching evidence material to guilt or punishment. Brady violations are not limited to documents stamped exculpatory. They include information that undermines the prosecution’s theory, supports an alternative theory, and changes how a juror evaluates causation, reliability, or credibility. This is exactly that category of evidence.

Suppressing or functionally neutralizing evidence that supports an alternative causal sequence in a vehicular homicide case is not harmless error. It is reversible-error territory. And that is why this is no longer merely a public debate about guilt. It is rapidly becoming a due-process case about whether a conviction was obtained under constitutionally compromised conditions.

The prosecution’s insistence on a fleeing-the-scene narrative played its role as a prejudicial multiplier. That allegation has an obvious psychological effect. It paints the defendant not merely as negligent, but as morally depraved. It primes jurors emotionally. It hardens public opinion. It makes the case feel simpler than it is. But legal systems cannot convict on disgust. They must convict on proof.

The fleeing narrative was advanced in ways that appear inconsistent with what the evidence supports and what the statute requires. If jurors were primed with an emotionally loaded theory that exceeded what the evidence could lawfully establish, it raises serious due-process concerns. The conviction becomes less about what was proven and more about what was implied. It becomes narrative punishment rather than legal adjudication.

Civil litigation is also exposing why certain witnesses were kept off the stand. Because in court, what you do not call matters. What you avoid matters. And sometimes the loudest evidence is the witness who never testifies. When law-enforcement credibility issues exist, disciplinary issues, competence issues, contradictions, procedural failures, those issues are impeachment evidence. And impeachment evidence is not optional in a fair trial.

The civil case removes that option. Depositions compel testimony. And once sworn, the record becomes permanent. Civil testimony strips away prosecutorial protection and forces answers long avoided, under oath, without the safety net of courtroom theatrics.

The legal reality is that reasonable doubt was not resolved, it was managed. This case contains irreducible doubt: a documented second-vehicle issue, unresolved causal sequencing, investigative narrowing inconsistent with best practices, missing physical evidence, unpreserved digital footage, and a prosecution theory dependent on jury insulation from destabilizing facts. That is not how guilt beyond a reasonable doubt is achieved. That is how verdicts are manufactured under controlled conditions.

And when a verdict requires controlled conditions to survive, it is not a stable verdict. It is a vulnerable one.

That is why this case will not stay buried under headlines forever. Civil litigation does not care about narrative comfort. It cares about the record. And the record is now revealing a legal truth that makes the Grossman conviction far more precarious than the public has been led to believe.

Two children are dead, and nothing written here changes that tragedy. But tragedy cannot be used as cover for a compromised prosecution. If the jury was deprived of key causation evidence, if Brady material existed and was not properly disclosed or admitted, if investigators narrowed the inquiry prematurely and evidence contradicting that conclusion later disappeared, then the conviction becomes what the legal system claims it never is: a result in search of justification.

And now the sworn depositions are doing what the criminal trial did not allow. They are restoring the missing questions into the record. They are exposing what was avoided. They are documenting what was not pursued.

Because the truth about this case was never fully litigated.

It was controlled.

Until now.

DISCLAIMER: Investigative reporting in high-profile litigation cases published by The Current Report is non-commercial, fact-based journalism; any project fees compensate research and reporting labor only, sources participate solely in accuracy verification, and final publication is approved exclusively by The Current Report after fact-checking is confirmed.